Monumental: Thinking Around the Meaning of Notre-Dame de Paris

Jonathan Long explores how the themes of identity and power inform Tomas van Houtryve's documentation of the rebuilding of the famous French cathedral after the 2019 fire.

After the April 2019 fire that destroyed the cathedral’s spire and most of its roof, Tomas van Houtryve was given rare access to Notre-Dame and the teams working to save the building from ruin. For over a year, he explored “the sacred, the grotesque, the graceful, and the defaced surfaces of Notre Dame, turning the monument into a prism for self-expression while documenting this historical moment of devastation and rebirth.” Tomas’ reportage was a cover story for National Geographic and part of The VII Foundation’s “Monumental” exhibition, along with Ziyah Gafic’s story on The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, shown during the Rencontres d’Arles this year. This article is based on Jonathan Long’s presentation at a panel discussion on the “Monumental” exhibition held at The VII Foundation’s Alexandra Boulat Campus in Arles on 5 July 2024.

How, when, and why did Notre Dame de Paris become a monument? What does Notre Dame de Paris’ monumental character mean for changing conceptions of, in the words of the exhibition curators, ‘faith, national identity, power politics, social cohesion, colonization, division, and political violence’?

Let’s begin by reflecting, for a moment, on the title of the exhibition: Monumental, deriving obviously from the noun ‘monument’. There are various related meanings of the word ‘monument’ in English (as in French and German). In its early usage, going back to the early fourteenth century, a monument was a tomb or sepulcher, later becoming a structure to commemorate the dead or something that, by its survival, commemorates and distinguishes a person, action, period, or event. It is only in the later eighteenth century that ‘monument’ came to mean a ‘structure, edifice, or (in later use also) site of historical interest or importance’ [my italics]. This, as we will see, is significant.

If we consider the adjective ‘monumental’, we see a narrowing of the focus. While ‘monumental’ can mean ‘of or relating to a monument or memorial structure’, this usage is quite rare. In its most common usage, ‘monumental’ means ‘Resembling or suggestive of a monument; like a monument, esp. in being large, solid, imposing, etc.’. and, in extended use, ‘comparable to a monument in massiveness or permanence; vast, stupendous.’

This may appear to be utterly self-evident and barely worth saying. Yet it cuts to the heart of the key questions underpinning the Monumental exhibition.

Notre-Dame de Paris and Gothic architecture

It could be argued that Notre Dame de Paris stands as a monument to the episcopal administration of Bishop Maurice de Sully, who commissioned the cathedral in 1163. Indeed, Wikipedia makes precisely this point. But this is a post-hoc construction; the fundamental purpose of Gothic architecture—of which Notre Dame is a pre-eminent example—was not the aggrandizement of its builders but the revelation of the divine.

But what did this mean for the largely illiterate masses of medieval Paris? Dany Sandron, speaking to National Geographic in January 2022, noted that ordinary people would have experienced the medieval church in a very different way from the Catholic Mass-goers of today.

Milling about in the chairless nave, they couldn’t see and could barely hear the services held by the resident canons, eight times a day, behind a wall in the choir. In the side chapels, chaplains whispered some 120 Masses a day, but those too weren’t really for the living; they were for the affluent dead, who had endowed Masses in perpetuity in hopes of boosting their souls out of purgatory. Nevertheless, ordinary people flocked to Notre Dame. They sometimes slept on the floor before an altar, dreaming of miraculous cures for painful diseases. Catholic faith was vital to most French people then.

This raises the question of how the Catholic faith could have become important to a populace that could not hear the masses being read in the cathedral and could not have understood them even if they had been audible because the language of the Mass was not the vernacular but Latin. Architecture provides one answer to this question.

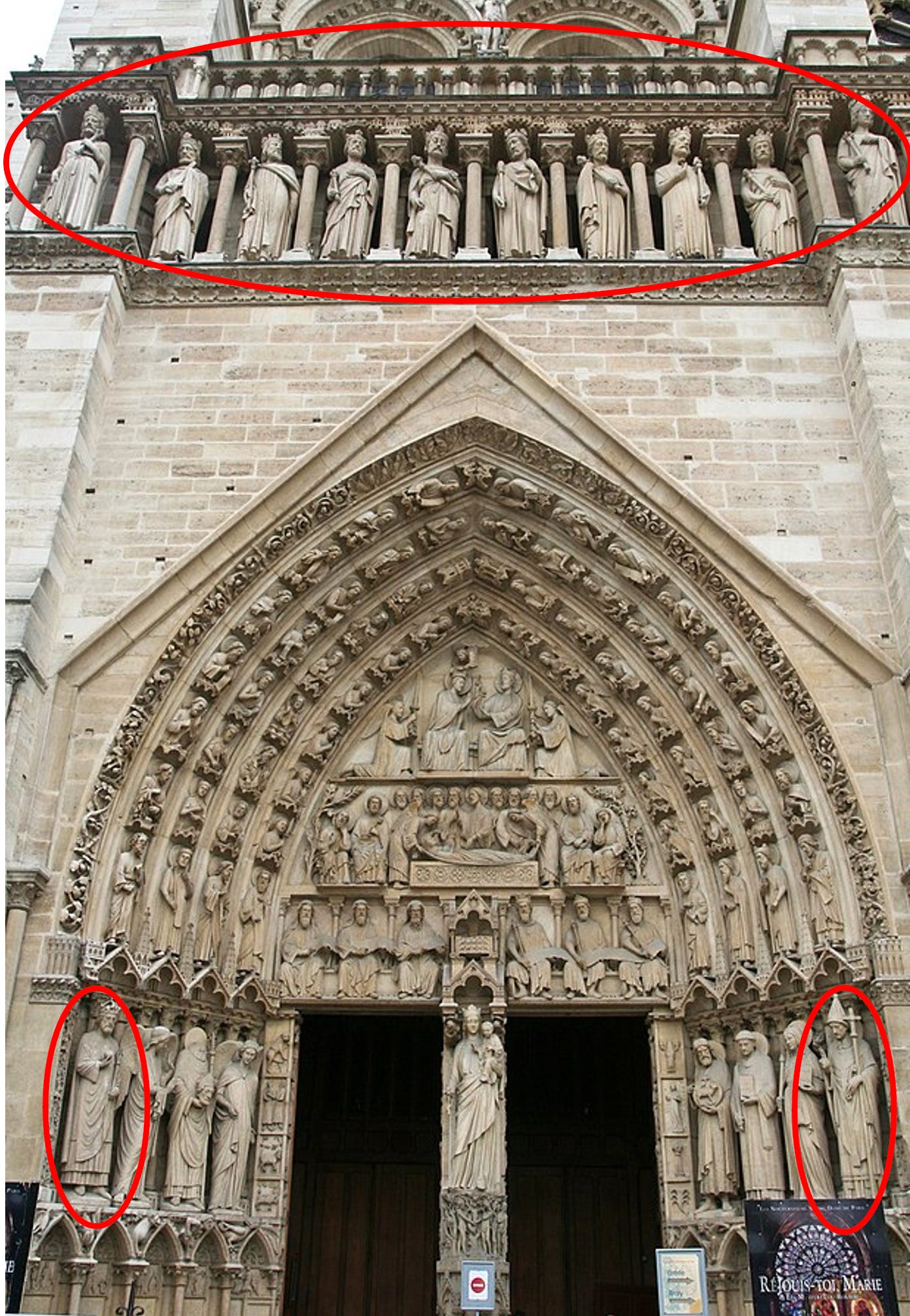

Approaching Notre-Dame de Paris today, we are confronted, as was the medieval visitor, by the massive West Front and its three portals.

These portals offer a visual distillation of essential religious dogma. The center portal is particularly explicit in its representation of the Last Judgment. We have to remember that in the Middle Ages, these sculptures were vividly painted, making them both more legible and more spectacular. The portals constitute a literalization of a parable from the Gospels (John 10:9: ‘I am the door. By me if any man enters in, he shall be saved’). In this way, they prepare the worshipper for the experience of the interior, which was itself an allegory of Heaven.

In his famous Outline of European Architecture, Nikolaus Pevsner identifies three architectonic features that define the Gothic style: pointed arches, flying buttresses, and ribbed vaulting. Pevsner understands the effects of these from the perspective of the ambulant visitor. Gothic building techniques enabled the construction of spaces that were longer, higher, and wider than their Romanesque predecessors. The walls were thinner, the windows much larger, and the interiors lighter in terms of both perceived weight and degree of illumination. Space was less obviously subdivided into bays, with the result that both the eye and the footsteps of the visitor were guided ever more seamlessly toward the altar and, thus, toward the most sacred space within the cathedral. There was more to it than this, however. The apparent weightlessness of Gothic structures meant that their interiors were flooded with diaphanous light. The interior of the Gothic cathedral was thus intended to enable worshippers to see beyond the visible and material world to the heavenly Jerusalem. The bodily experience of light was deemed to be the gateway to a transcendent experience of divine illumination.

Art historian Bernd Busch notes that this had two effects: On the one hand, the majestic manifestations of religious imagination in Gothic architecture responded to ordinary people’s need for sensory experience and emotional identification. On the other hand, the calculated concretization and making visible of the specific tenets of the Christian faith was an act of cultural colonization in the way it shaped and guided the emotional lives of the faithful. Even at the time, medieval heretics rebelled against this, arguing that the spectacular nature of religious buildings and ceremonies was ultimately a form of propaganda and persuasion: it emancipated the senses only to instrumentalize them for purposes of social control.

In fact, this social control was not solely a question of religious doctrine but of concrete and visible hierarchies. The cathedral’s construction instituted a rigorous separation between the choir, which was accessible only to the bishop, canons, and those responsible for celebrating the liturgy, and the nave, which was accessible to all. Furthermore, within the choir, the spatial distribution of bodies was in strict accordance with the rank of those present, from the bishop downwards.

Ecclesiastical power, then, was inscribed in the very structure, decoration, and spatial layout of Notre-Dame de Paris. So, it turns out, was royal power. While not part of the original intentions for the cathedral, around 1220, it was decided to thin out the masonry surrounding the portals in order to accommodate the Gallery of Kings. This row of twenty-eight statues nominally depicted the kings of Judah before Christ. But even in the thirteenth century, it was interpreted by visitors as representing and exalting the kings of France. The intimate link between ecclesiastical and royal power was underscored by a list of the monarchs of France, starting with the sixth-century King Clovis, which was affixed to the cathedral door at around the same time. Notre Dame de Paris was also rapidly integrated into the legitimating ceremonies of royalty. Each new sovereign stopped at Notre-Dame de Paris after his coronation in Reims to give his solemn vow before the bishop and chapter to ‘respect and protect the privileges and liberties of the Church in Paris,’ as Andrew Tallon and Dany Sandron note in their book Notre Dame Cathedral: Nine Centuries of History. Furthermore, the North Portal, known as the Portal of the Virgin, is flanked by statues of Emperor Constantine – the first Christian Emperor – to the left and Pope Sylvester I to the right.

‘In the eyes of medieval spectators,’ write Tallon and Sandron, ‘these figures illustrated the virtue of a political system in which royal power and ecclesiastical power were inextricably linked.’

If we think, then, of the power politics encoded in the Gothic cathedral at the time of its construction, it was not simply a question of awe-inspiring scale (cathedrals dwarfed the dwellings and other buildings of the medieval city) but of three further interlinked functions:

First, the concentrated visual and sensory expression of a univocal understanding of the divinely ordered cosmos; second, the visible performance of social hierarchies through spatial division and the distribution of bodies; and third, the visual representation and periodic ceremonial reinforcement of the link between monarchical and ecclesiastical power.

The fact that the Gallery of Kings was added in 1220 may suggest something more, too. It falls towards the end of the reign of Phillip II, also known as Philip Augustus. Philip Augustus had won a famous military victory at Bouvines in 1214, defeating a coalition of King John of England, the Holy Roman Emperor, and the Dukes of Flanders and Burgundy. This had strengthened the power and prestige of the French Capetian monarchy throughout Europe, and during his reign Philip brought large areas of French territory under direct or indirect control of the French crown. He was also the first monarch to style himself as ‘King of France’ (Rex Franciae) rather than ‘King of the Franks’ (Rex Francorum). This ostensibly minor change in nomenclature actually represented a decisive shift that mapped the monarchy not onto a people – the Franks – but onto a territory: France. The political ties between church and crown symbolized by Notre-Dame de Paris were, from the beginning, inextricably linked to the drive towards unified, centralized French nationhood.

Notre-Dame fulfilled these functions not as a monument but as a living building, a building for use. But it’s important to note that its effects of power depended on visuality, on making specific visual and sensory experiences available to the faithful.

The emergence of the monument

I’m now going to fast-forward six centuries to think about the ways in which modernity has inflected the function of Notre Dame. The specific features of modernity that I will focus on are political democracy, secularism, and the emergence of the technical media. And I will tie these things back to the questions that animate the Monumental exhibition. These, to remind us, are ‘faith, national identity, power politics, social cohesion, colonization, division, and political violence’.

The French Revolution of 1789 led to profound changes in the function of ecclesiastical architecture. Church property had been nationalized in 1789, meaning that the French state now bore responsibility for its future. Destruction and looting of royal, aristocratic, and Church property were widespread and were at times tolerated – even officially advocated – by administrators and lawmakers. Notre-Dame de Paris was not exempt: amid the violent upheavals, it was severely damaged, and the Gallery of Kings was dismantled by revolutionaries who, like their medieval forebears, believed the figures to represent the Kings of France. And yet, as Anthony Vidler notes in his book The Writing of the Walls, alongside this sanctioned destruction, there was ‘an emerging sensibility towards a national patrimony embodied in historical and artistic monuments’.

In a series of reports to the Convention (the post-revolutionary governmental assembly) in 1794-5, Abbé Grégoire, Bishop of Blois, coined the term ‘vandalism’ to designate hostile acts towards property. He went on to declare that French Gothic architecture was ‘one of the most daring conceptions of the human spirit’ and an aid towards ‘happiness in being French’. ‘In the name of the nation (patrie)’, he continued, ‘let us conserve the artistic masterpieces. The Convention owes it to its own glory and to the people to hand down to posterity both our monuments and its horror at those who wish to annihilate them.’ Using the term ‘monument’ in the distinctively modern sense of ‘buildings of historical significance,’ Grégoire effectively stripped away the theological significance and political instrumentality from royal and religious buildings and artifacts. No longer linked to a specific faith community or a political elite, the buildings of the past – especially French Gothic architecture – were recategorized not as living embodiments of power but as the universal cultural heritage of the French nation.

This ‘vaste réorganisation du patrimoine culturel’ (Daniel Hernant) was a crucial move, for the reassessment of the monarchical and ecclesiastical past was vital for legitimizing the newly-democratic French republican state. In short, France needed to re-envisage its own history in ways that rejected affirmative narratives of dynastic continuity and political Catholicism.

Abbé Grégoire’s pronouncements quoted above—about vandalism, the human spirit, and the French nation—imply two complementary aspects to the preservation movement in post-Revolutionary France. The first was concerned with safeguarding and restoring buildings that were deemed to be both historically important and at risk. The second was concerned with constructing a kind of imaginative historical geography of the French nation based on ecclesiastical, royal, and aristocratic buildings that were now, as it were, reclassified as historic monuments.

In contrast to other European countries, historic preservation in France was notable for its high degree of centralization and state coordination, which began in the 1790s and continued throughout the nineteenth century. Across various state agencies, museum experts, archaeologists, cartographers, and historians set about collecting, documenting, and reevaluating the materials of the French past and putting them on display. Image-making was central to these projects in the form of drawings, paintings, engravings, lithographs, and maps. The invention of photography massively expanded the potential role of images for the advancement of the preservation agenda.

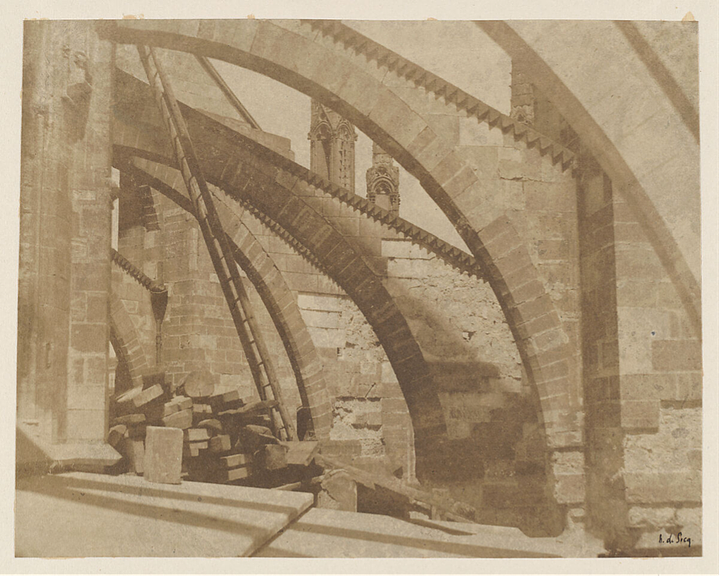

From the point of view of architectural restorers, detailed records of the condition of buildings, their construction methods, and distinctive features were essential prerequisites to the work of conservation and reconstruction. Photography—and especially the Daguerreotype—could accomplish this task with a level of speed and accuracy that was beyond human capabilities.

From the point of view of patrimoine, on the other hand, disseminating photographs of historical monuments was part of a broader ongoing effort to produce national unity – and thereby social cohesion – by exposing viewers repeatedly to artifacts from the shared past. Historian Susan Crane notes that visiting museums or historical sites forces one to participate, however momentarily, in the ‘public’ that is constituted by shared historical knowledge. The same applies to viewing photographs: monuments of the past could be displayed in ways that reminded the French public of its common, collective heritage. But because photographs can circulate and make geographically dispersed sites available for visual consumption anywhere, they reinforce that sense of national belonging on a much more regular basis than museum or sightseeing visits.

In saying all this, I have tried to think about the emergence of the historic monument in post-Revolutionary France, the role of these monuments in constituting a new national past, and the importance of photography as an indispensable adjunct to this nation-building project. In the final part of this post, I’d like to return to Notre-Dame de Paris, looking at its nineteenth-century history before concluding with some comments on the Monumental exhibition.

As mentioned earlier, Notre-Dame de Paris was sacked during the French Revolution. For several years afterward, it was used as a warehouse. It was restored to the Catholic Church as a result of the Concordat of 1801 between the Holy See and Napoleon, and Napoleon crowned himself Emperor of France in the cathedral in 1804. By the end of the Napoleonic era, however, Notre Dame had fallen into a state of dereliction. It was subject to further vandalism and an arson attack during the 1830 revolution, and its condition became so parlous that demolition was considered. According to popular myth and many a website, the publication of Victor Hugo’s Notre Dame de Paris – translated as The Hunchback of Notre Dame – in 1831 drew attention to the building’s importance and reignited French enthusiasm for Gothic architecture. What we know for sure is that Hugo was a tireless campaigner for the preservation of French architecture and that he used language that was entirely in line with the argument I’ve been making about monuments and the nation. In an essay of 1832 published in Revue des deux mondes, he wrote:

What we’re actually suggesting, therefore, is that in France right now, there may not be a single village, a single capital of an arrondissement, a single main town of a canton, where the destruction of some historic national monument [my italics] is not being planned, begun, or completed.

For Hugo, as for many of his compatriots, the conservation of historic buildings was very much seen as a question of preserving the national past. The campaigns to which he contributed eventually led to the lengthy, expensive, and controversial restoration of Notre Dame under the supervision of Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc.

The restoration took place simultaneously with the so-called Haussmannisation of Paris. Baron Haussmann, the Prefect of the Seine under Napoleon III, masterminded the large-scale transformation of Paris throughout the 1850s and 1860s. Haussmann drove expansive arterial boulevards through the city, destroying old neighborhoods, which, in many cases, dated back to medieval times. In terms of new construction, Haussmann was far less interested in individual buildings than he was in the street and the circulation it enabled. However, in terms of older architecture and buildings of symbolic importance, he pursued, as Shelley Rice notes, a policy of dégagement or disencumberment: the isolation of public buildings in space so that they could be clearly viewed.

In the case of Notre-Dame de Paris, Haussmann quadrupled the size of the parvis, the square in front of the cathedral, and demolished the ramshackle dwellings that had previously covered much of the Île de la Cité. Notre Dame could thus now be viewed across a large expanse of empty space in splendid, monumental isolation. It had always been possible to represent the West Front in this way – in painting and also in photography, as in this image by Henri le Secq.

Haussmann transformed the monument's isolation from an aesthetic possibility into a lived optical reality. As we saw earlier, the cathedral’s function in the Middle Ages depended on the multiple forms of visuality that communicated divine grace and earthly power. As a historical monument, too, its power cannot be divorced from its status as a visual spectacle.

Monumental

In The VII Foundation’s Monumental exhibition, the function of Notre-Dame as a national monument is the jumping-off point. The visual contextualisation includes an anonymous photograph of the cathedral, with crowds awaiting the arrival of General de Gaulle after the liberation of Paris in 1944. The West Front is festooned with tricolore flags and the insignia of the Free French.

Yet there are some significant differences between Tomas van Houtryve’s work and the photographs of the cathedral’s nineteenth-century restoration.

While the likes of Henri le Secq and Gustave le Gray dwell on masonry yards and imply the labor of individual masons shinning up and down ladders to repair stonework, Tomas van Houtryve’s images emphasize the restoration project's huge scale and technical ingenuity.

This can be made quite spectacular in itself, as in this image, which foregrounds scaffolding and a huge tower crane.

The fact that van Houtryve took this image with a nineteenth-century camera using the wet collodion process produces a strange historical disjunction, with the outmoded technique existing in tension with the state-of-the-art approach to restoration. In a night-time shot made with modern equipment, the partially reconstructed cathedral is spectacularly illuminated, constituting the restoration work as something to be looked at and marveled at.

This emphasis on technology, however, goes hand in hand with a concern for artisanal skill and the sourcing of materials from French quarries and forests. This roof truss, made from French oak and using medieval tools and methods, celebrates both the skill of the cathedral’s original builders and the persistence of such crafts in the present day.

This is very much in line with how France has understood the nature of its own modernity since the late nineteenth century: on the one hand, a country in which artisanal skill is still prized, and on the other hand, a country at the vanguard of technological progress.

A further distinctive feature of van Houtryve’s photographs is the concentration on the religious function of Notre Dame. A photograph showing paintings of biblical scenes and stained glass is not something we find in photographic records of the nineteenth-century restoration. The ecclesiastical function of the cathedral is not, admittedly, writ large in van Houtryve’s project. This becomes very clear when we compare it with Ziyah Gafič’s photographs of the Dome of the Rock in the same exhibition. Gafič’s images are full of people, and his long exposure times show that these people are moving to, from, and around the building. Alongside the mosque’s stunning beauty, Gafič emphasizes its constant use as a place of worship and a site of political protest. But by thematizing the religious function of Notre-Dame to at least some extent, van Houtryve gestures toward some interesting aspects of the current restoration project.

At present, visitor numbers to Notre Dame de Paris say a lot about its significance: it attracts about 3,000 weekly mass-goers, but around 12 million tourists per annum. Its status as a monument of historical and national interest massively trumps its status as a devotional site. In the immediate aftermath of the fire in 2019, the vast preponderance of newspaper reports in the French media stressed Notre Dame’s national importance rather than its significance for the Christian faith community. And, of course, Emmanuel Macron’s immediate commitment to restoring the building turned it into a concern of the French state. The fact that he brought retired five-star general Jean-Louis Georgelin out of retirement to run the project is also telling, but so, perhaps, is the fact that the General is a devout Catholic: a kind of military-ecclesiastical complex in which faith is seen as an integral part of the state-sponsored restoration.

When Notre Dame de Paris reopens, there are plans to re-curate the visitor experience. People will be guided in a new loop from north to south, from dark to light, encountering the Old Testament and then the New. Patrick Chauvet, rector of the Cathedral, told National Geographic that the visitors will thereby enter progressively into the mystery of God. This, it seems to me, is nothing less than a reanimation of the spatial dimensions of the cathedral to convey a theological message. We are, as it were, back in the Middle Ages. Whether this still works in the twenty-first century, however, remains to be seen.

Postscript

Protesting the destruction wrought on Strasbourg cathedral after the French Revolution, Abbé Grégoire declared: ‘A Strasbourg au xviiième siècle on a surpassé les Alains et les Sarrasins’ (‘At Strasbourg in the 18th century, we have surpassed the Alans [a nomadic tribe from the Caucasus] and the Saracens’). ‘Saracen’ was a pejorative term for Arabs, and the implication was that the peoples of the Middle East were uncivilized barbarians. There was some irony in this, for as Diana Darke notes in her book Stealing from the Saracens, many features that are considered typical of the Gothic style, including pointed and trefoil arches, have their origins in much earlier Islamic architecture. Indeed, the earliest known use of the pointed arch is in the internal colonnade of none other than the Dome of the Rock.

While the Monumental exhibition very much foregrounds the status of Notre-Dame as a historic monument of the French nation, juxtaposing it with the Dome of the Rock also hints at another history. It is a history of cultural diffusion and its ineluctable relationship to political violence and colonization – not necessarily in the form we might expect, but in the form of the Muslim conquest of Spain in the early eighth century and subsequent Arab expansion into Sicily, Italy, and Southern France. A building that seems to be the very epitome of Christian northern Europe owes its very form to the highly sophisticated culture that developed in the Arab world when Europe was still on the periphery of the civilized world.

Jonathan Long is a Professor in the School of Modern Languages and Cultures at Durham University in the UK. He was a founder member of the Durham Centre for Advanced Photography Studies and is co-director of the Centre for Visual Arts and Culture.

Jonathan has published extensively on twentieth-century German and Austrian literature, including acclaimed monographs on Thomas Bernhard and W. G. Sebald, and articles on Bertolt Brecht, Wolfgang Hildesheimer, Monika Maron, Gerhard Fritsch, Hans Lebert, Dieter Kühn, and others. Jonathan is currently researching the photographic book in the Weimar Republic, among other topics.