Multidisciplinary artist Ngadi Smart will tell you she always has something to do. With a keen eye for truth and community, Ngadi’s creative objectives reflect this, creating various projects spanning a range of media, from documentary photography and illustration to moving images and mixed media art.

Sierra Leonean Artist Ngadi tethered herself to the arts at an early age. She exhibited an aptitude for the culture of practice, which informed her tertiary studies in art and design in Canada, Côte d'Ivoire, Tunisia, and the UK, where she now lives and works some of the time.

American poet Quincy Troupe once wrote, "photography is an art form executed by photographers who are also extraordinary artists." This rings true with Smart’s portfolio, which includes topical illustrations for The Atlantic, The Guardian, and publishing houses such as Penguin’s Riverhead Books and Faber’s Children, as well as photography published by CNN, British Journal of Photography, Vogue Italia, Atmos Magazine, and I.D Magazine.

Ngadi's journey into the visual arts began as an exploration of identity, with her portfolio reading like a mosaic of the human experience. In an interview with Ngadi for Dispatches, it was clear that community is front and center in her work. "I have always wanted to show all the different ways it means to belong to a group," she said. Her work is timeless, poetic, haunting, and powerful. Having developed this style over the years, Smart has a remarkable ability to encapsulate raw emotions and untold stories from her communities within her images. Through deft use of texture, composition, and meticulous attention to detail, her work goes beyond aesthetics and forges genuine connections.

Ngadi’s practice is a story of years spent examining layered occurrences—moments when figures embellish, textures shift, light distorts color, jewelry folds, and opposites unite. Experimentation and adventure mark Ngadi’s fascination with belonging as it stretches across form and mood. This is the domain of the inquiry, the study, scouting the unseen. Lessons from her early life, pop culture, and an intrinsic interest in the visual arts continue to shape Ngadi and her inquisitiveness. Ultimately, she harnesses the inexhaustible property of curiosity to fuel her work.

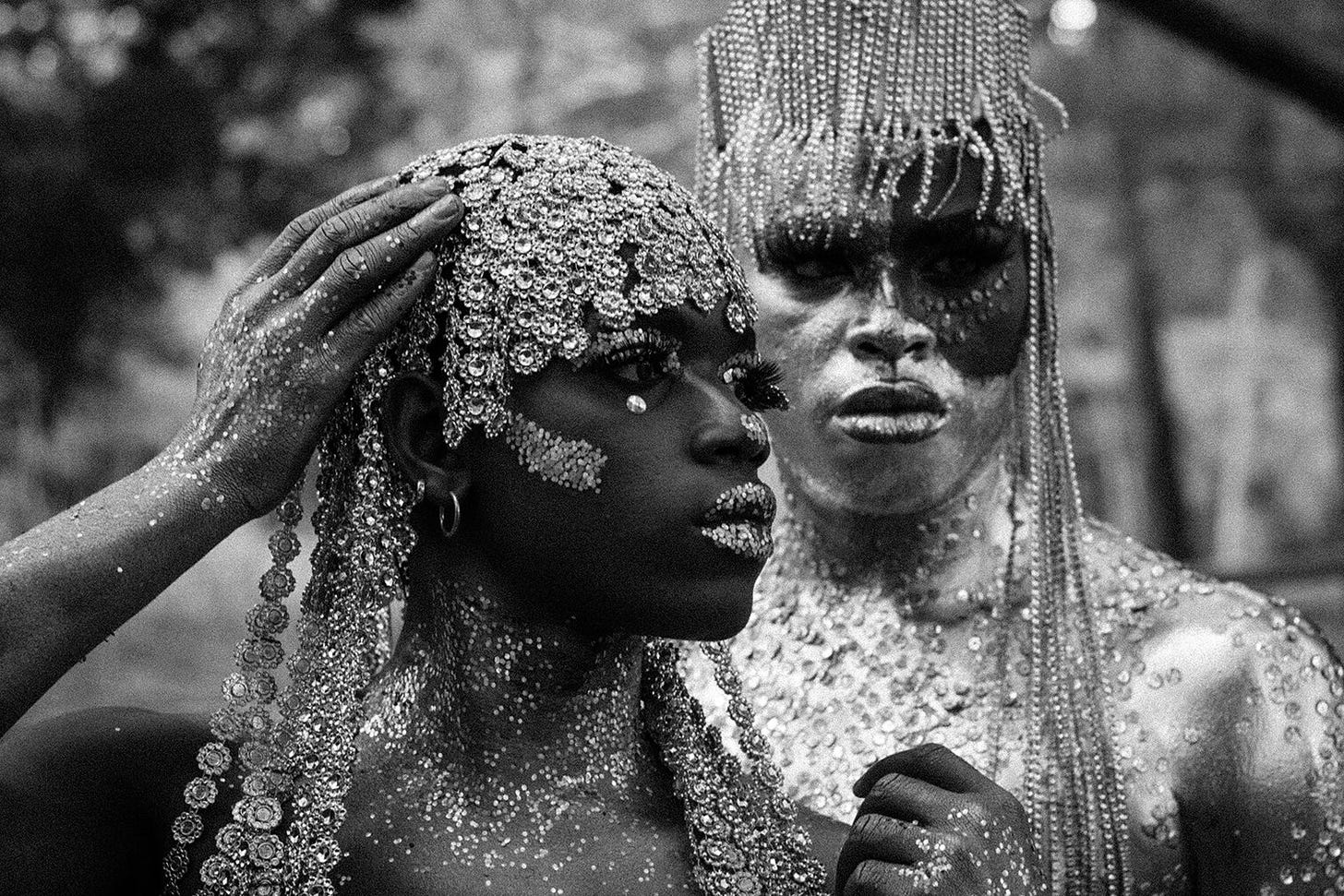

In The Queens of Babi, Ngadi photographed Abidjan's drag artists and performers Kesse Ane Assande Elvis Presley–also known as "Britney Spears" to her friends–and Mohamed, aka "Baba," for a collaborative series to highlight their talent and creative passions. “I hope my work changes at least one person’s perception,” Ngadi told It’s Nice That, “and frees someone from what they’ve been socially conditioned to believe.”

Despite being often seen as objects of disgust or ridicule, drag queens, especially in African countries, use their artistry to speak out about issues that matter to them, such as housing and health care rights. By photographing them, Ngadi celebrates queer creativity and resilience. This body of work has been exhibited in various exhibitions worldwide, including Kyotographie ‘21, where Ngadi showcased the different ways in which Black people can simply be.

Throughout the history of the visual storytelling of African people, the sense of boundless opportunity has been rarely represented. During colonization and slavery, African people were rarely portrayed as producers of their own image, and the camera was often used as a tool of oppression. Ngadi Smart accepts the challenge. She prefers working alongside the people she photographs, telling Shorthand.com that "it's better to let the person who's being photographed have some control over the way that they're portrayed."

Smart's images offer a human dimension, a critical perspective from which to envision ourselves as human beings who will all experience life’s tragedies, including the effects of the climate crisis, regardless of our demographics. Her photographs are often characterized by their stark textures and their unflinching depiction of the resilience of nature and the communities she works with. From her ongoing project C’est pas Fini, recording the coastal erosion caused by climate change in Grand-Bassam, Côte d’Ivoire, Smart presents the harsh realities of climate change. But she also reveals how communities are already adapting to a new world.

In one of her images from the award-winning project Wata Na Life, commissioned by WaterAid and the British Journal of Photography, Ngadi shows the Guma Dam, which supplies over 90% of Freetown’s water. However, rather than simply reflecting a drying dam, Ngadi created a new perspective using mixed media. The resulting image stands out stark and loud, with the spatial delineations of a stylized sculptural figure with long, flowing limbs.

The black and white photograph, married with this illustrated form, presents the Guma Dam as barely living to its potential due to something it can not contain. The state of the dam, Ngadi says, “is due to the rise in temperatures, which is depleting natural water resources and is basically causing a drought.” What is being experienced by Freetown residents is a result of climate change. The figure appears to be emerging from the water, its form suggesting both power and vulnerability. “These communities do not have a high carbon footprint, and their suffering is also exacerbated by other nations' high carbon footprint and continual plundering of natural resources,” she adds.

This image is part of the multimedia work that speaks to the adaptability of these communities in Sierra Leone as they confront the climate crisis. Ngadi collaborates with the community by asking them to bring in their favorite items that demonstrate the skills they use to contribute to community well-being. Ngadi then uses pose, gesture, light, shadow, texture, form, and contrast to build scenes that set forth a series of community responses to the climate crisis. “You adapt, or you give up and die,” Ngadi says. “The more all of us put pressure on this, the better for all of us.”

“During my project Wata Na Life, collaborating with the communities in Sierra Leone was also essential in displaying some of their personalities and creative talents, such as with the Taninawahun community, who created accessories out of cocoa leaves from the cocoa they farm daily, so I could photograph them in something they were so happy to show off.”

These photographs serve as an index to the narrative that the community plays a vital role in adapting to the impacts of climate change. “People just want to have the adequate tools for them to work in their community to improve it.”

Ngadi's work is a departure from the colonial role of photographers as voyeurs, as she engages in collective creativity with those she photographs. In Wata Na Life, Ngadi wants us to look and “become aware of what’s going on and that hopefully governments and international organizations can empower – not just fund – but properly empower the people in Sierra Leone,” Ngadi concludes.

This is the first article in a new series, Postcolonial Perspectives, written by Fiona Wachera, showcasing new photography from Africa; photography and visual stories that foreground embodied experiences and challenge colonial histories.

Wachera is a media strategist and the photo editor at Everyday Africa. Their work blends hands-on design for photo, art direction, and media project management, utilizing varied communication mediums, design disciplines, and research techniques. Wachera has collaborated with storytelling teams at the World Press Photo Foundation, Black Women Photographers, Code For Africa, the ICRC, and others.