Creating a novel representation of the atrocities committed during the ethnic cleansing campaigns of the Bosnian War is no easy task, but Ismar Cirkinagic's Herbarium project offers a powerful and original account.

The project began in 2004 and is based on a classical herbarium that classifies flora. The difference is that all the plants have been collected from the site of mass graves in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The plants are gathered, dried, and mounted behind glass, along with information about the mass grave site. Cirkinagic has made 70 new pieces specifically for the new exhibition in Sarajevo.

The exhibition was a project of The VII Foundation, managed by VII Academy in Sarajevo, with the Danish Arts Council, Memory Module, KUMA International, the Museum of Contemporary art Ars Aevi, and The National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina as partners.

Claudia Zini interviewed Ismar in Prijedor this October, prior to the opening of his exhibition in Sarajevo.

What are your name and profession?

My name is Ismar Cirkinagic, and I work with visual arts.

Where are you from?

I was born in Prijedor, at that time Yugoslavia, in 1973. In the autumn of 1992, I left for Denmark. Now I live between Prijedor and Copenhagen.

When did you return to Prijedor for the first time?

I returned to Prijedor in 1998, six years after the beginning of the war. I was curious and wanted to come back. At that time, some people still lived in our house, and it was occupied, so I stayed in Sanski Most at my neighbor’s, who had managed to save their house in Prijedor throughout the war. He would often come to Prijedor because his parents still lived there. At that time, people didn’t cross these borders much. Coming back in 1998 was adventurous, a safari. Mass murderers were still on the streets. Everyone was there; the party was still going on. My parents tried to stay in Prijedor. They didn’t leave until 1995. You couldn’t just leave. You could try in a convoy, but it could happen the same as with Kori?ani Cliffs when a convoy was stopped and people were separated and killed. Would you take that gamble? Otherwise, how are you going to leave? Of course, in the case of indisputable violent deportations, there was no choice. The idea of ethnic cleansing is to permanently remove an ethnic group from a specific area. The aggressors, therefore, make the situation unbearable for the targeted group. People were afraid to stay but also afraid to leave because they knew leaving was equally dangerous. It was their home. It is a struggle between leaving and staying.

How did you start working on Herbarium?

The first idea came about around 2004. In the beginning, I would photograph landscapes around Prijedor that could be mass graves connected with ethnic cleansing and mass executions. Very few mass graves had been opened at that time. Mass graves could be anywhere. At that point, very few people had been found out of the more than 3,000 that were reported as missing from the Prijedor municipality. In the very beginning, I would wander around nature and ask myself, is there a mass grave there? Soon enough, I met some people who worked on the exhumations, and from then on, they directed me to the right locations when I needed them. I would photograph the same locations again and again. While photographing mass graves and execution places, I asked myself, what kind of plants are there? I noticed that nature has its tempo. Over time, those locations would change drastically. One day there was just soil covering the mass grave; the next day, the site was filled with grass. Three years after, trees would cover the area. It was obvious for me to start thinking of the flora and its role in that specific situation.

Which locations did you visit to make this last Herbarium?

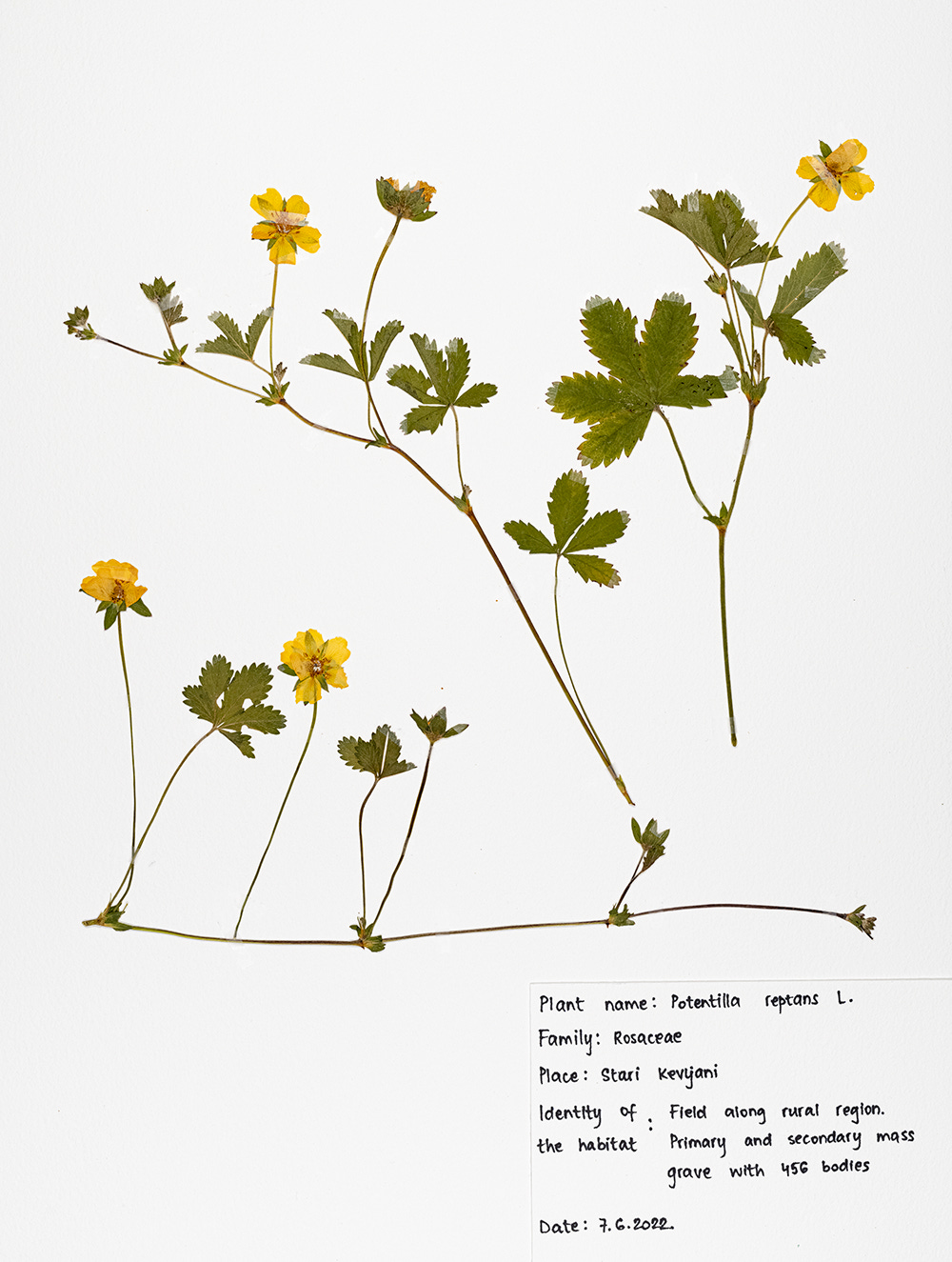

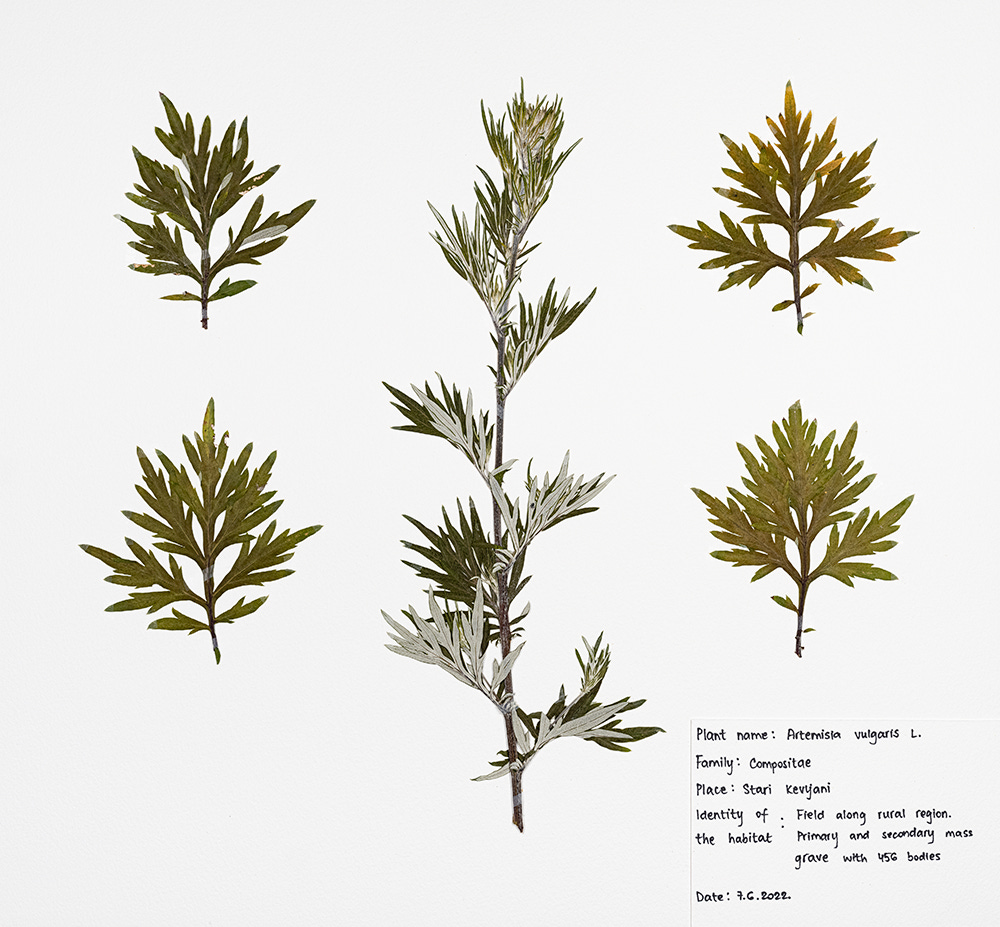

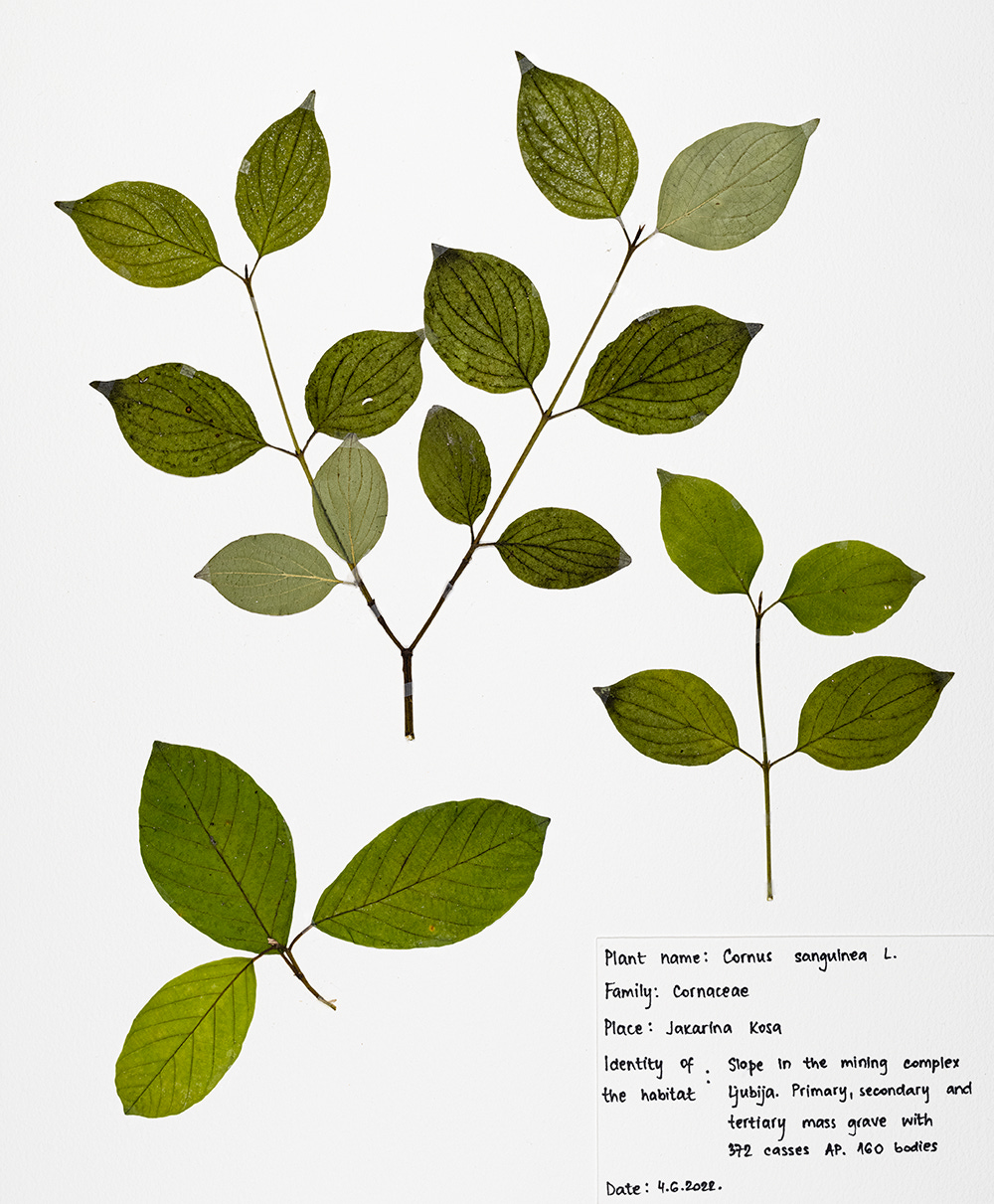

I visited four locations: Tomašica, Stari Kevljani, Jakarina Kosa, and Dizdarev Potok. Tomašica is a primary mass grave, a dump on the hill “Depo” close to a large mining complex. It is one of the single largest mass graves in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Its exact location was revealed by a former Bosnian Serb soldier who took part in the cover-up of the killings. Its location remains unmarked. Dizdarev Potok is a primary mass grave by a creek near the forest, with bodies of people from villages around the mining complex of Ljubija. Jakarina Kosa is a primary, secondary, and tertiary mass grave, also located in Ljubija, while Stari Kevljani is a primary and secondary mass grave located in the village of Kevljani, 20 kilometers from the city of Prijedor. I started photographing the area around Tomašica around 2003. Ten years after, when they discovered the mass grave there, I visited it again with Darko, one of my childhood friends, and my two dogs around sunset. There was the weirdest light, very dramatic. It looked almost unreal. There was a hole recently excavated, maybe four or five meters deep, a pile of soil on the side, robber gloves and tape, and smell from the mass grave. They must have found something again, and I told Darko. We went home, and the first thing on the news was the discovery of ten more bodies. In the following days, the exhumation continued, and the bodies suddenly started piling up in hundreds. On the way to Tomašica are a number of houses owned by local Serbs. If you come with trucks and you have a lot of dead bodies, people will notice and, of course, complain. They didn’t want those bodies in the land that surrounded them. Perhaps that’s why local authorities decided to remove some of the bodies from Tomašica and bring them to Jakarina Kosa. They were under pressure from the locals who knew those bodies were coming from the surrounding Muslim and catholic villages. Authorities didn’t want the locals to be unhappy. They knew if nothing was done by local Serbian authorities in the meantime, that could lead to locals going and denouncing that there were bodies on their land to someone from the Hague or someone from the justice court.

What is the process of making a herbarium?

The process is reasonably simple, something we learn as kids at school. The plants I choose are pretty healthy and, if I’m lucky, in a state of blooming. I collect the plants, dry them, put them on a clean sheet of paper for seven days, add pressure to it, change the paper after seven days, leave it for two weeks, and after that, put it on another sheet of paper for three weeks, and so on until the plant completely dries. It usually takes around six weeks. My approach is not very classical. For classic herbariums, people usually pick whole plants from the roots. The plants I choose to collect have certain aesthetics, almost graphic aesthetics. This is art. It is not necessarily a pure example of botanical knowledge, nor is it to be used for scientific study. It symbolically reflects specific ideas, adding graphically pleasing elements to it.

Did you collaborate with other people on this project?

Yes, I collaborate with a couple of people while collecting plants and often talk with people working on exhumations. Darko Draži? is a childhood friend who has been helping me from the beginning, learning with me what had happened. He would always bring a camera with him and photograph me while collecting the flora. It was an unexpected help.

What did you learn about the flora growing on mass graves? Did something change in terms of vegetation structure and species composition?

Some plants started to repeat and come to me again and again. I learned their names and families. No matter how uninvolved you are with botany, you will have to learn certain things about it. Take blackberry, for example. When I brought it to Copenhagen to the Botanical Garden for the first time for examination, they told me it was not simple blackberry. There are several different varieties within each family. One of the questions people would ask me is this “ghostly” thing: do flora grow taller on the site of a mass grave? I don’t know. You see flora there, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that the decomposing bodies fertilized it. I think people like to believe that there is a connection between the bodies and the plants in some dark symbolic prediction. It is possible that when removing bodies from one place to relocate them in another place, seeds were also brought from one location to the other, but there is no evidence that the flora here has changed just because of the bodies. This is a rather small area, so sometimes you find the same plant growing in two locations. But then again, some of the plants are very typical for the location. In a couple of places, we found strawberries. There is a plant Darko calls vodolija, which grows only on Dizdarev Potok because the creek is always humid, and that plant likes humidity. There was a grave in Dizdarev Potok, and according to what I heard during the exhumation, ten people were buried very close to the creek. During spring and autumn, the water level would rise and cover the mass grave so that the site would additionally be disguised, and nobody would notice. The creek would flood, and it would be almost impossible to get to the bodies. Whether it was done on purpose, it’s hard to say. I guess not; countless cases point to the fact that they weren’t that smart. The landscape here changed enormously. It is drastically changed from when I first photographed it years ago. It changed a lot since I was here in spring; most of the nettles and blackberries were not here. Nature changes dramatically, and over time, it simply takes over. I see changes in nature as a metaphor: the dying, the decomposing, soil takes over your body, and then minerals from your body are taken by the plants.

What is specific about this latest version of Herbarium?

I was first contacted by VII Academy in November 2021. In April 2022, I came to Prijedor to start working on this latest version, but very few plants were flowering at that time. I collected the last plants in August and made 70 pieces specifically for the exhibition at the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo. The exhibition will open at the National Museum 30 years since the war started, a round number. Thirty years is not a little time. We are still living in the war in many ways. There are still traces of the war around us; we are still looking for bodies of people missing, discussing certain topics. There is, again, a new cycle of nationalism. We obviously didn’t leave those demons from the past behind. After the show, some of them will remain at the museum, which has one of the most extensive collections of herbariums. It is nice to know that it will be shown in Bosnia and Herzegovina for the first time since I first started working on this project eighteen years ago.

Is there a message you want to convey to the audience through your work?

I don’t have a message for the public. People who want to know what happened in the war know about it by now. I make art for myself, trying to solve some questions I have. There is a certain truth or things I want to find. I don’t do it for an audience. Afterward, when the work gets to the public, it has a life of its own.

Claudia Zini is an Italian art historian and curator focusing her professional interests on visual arts dealing with the aftermath of war and violence. She is the founder and CEO of Kuma International Center for Visual Arts from Post-Conflict Societies.

Claudia holds a Ph.D. degree from the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. In 2019 she was one of the curators of the Pavilion of Bosnia and Herzegovina at the Venice Biennale. She is the co-editor of the book “Sarajevo Unfolding” (Buybook 2020) and “Unsafe Goražde” (Kuma international, 2022). In 2022 she produced the documentary film “Unsafe Goražde.” Claudia lives and works in Sarajevo.