On 5 March 2022, ten days after Russia had unleashed its war on Ukraine, several photographs and reports emerged from a bridge in the northwest of Kyiv that connects the capital with a small city nearby, Irpin. Ukrainian forces had partly destroyed the bridge to prevent possible Russian invaders from using it to attack from that direction. Now, people from Irpin had sheltered underneath its vast concrete structure before they were made to cross the river over a very flimsy-looking wooden board.

On Instagram, Jedrzej Nowicki and Emilio Morenatti both published photographs of the event. The photographers’ vantage points were very similar. Nowicki’s photo showed a wider scene, with people streaming toward the viewer. Morenatti had zoomed in closer onto the bridge itself, with people still constrained by Ukrainian forces. Later that day, I watched two separate news reports on the same event, one by CNN (US), the other one by Der Spiegel (Germany).

Since the 2011 war in Libya, I have tried to collect information from as many sources as possible. In a nutshell, I’m trying to perform a very simple, poor-mans version of verification and cross-correlation. Unlike professional organizations like Bellingcat, I cannot verify what I see (even as these days, with every piece of information from a war zone, I attempt to find at least one other independent report about it). Instead, as someone interested in photography, I am interested in learning more about how photographs are made, shared, and interpreted. As it turned out, in 2011 already, the same event might have been photographed by more than one photojournalist, offering interesting insight. For example, in the case of Libya, I found one scene that had been photographed by four photojournalists at more or less the same time: a single rocket launcher firing. Three of them must have stood right next to each other; another had been at a distance. From the three closer pictures, it wasn’t possible to tell what had actually gone on. The view from afar showed that there had only been that one rocket launcher.

Coming back to the scene at the bridge, I shared the two posts by Nowicki and Morenatti in my Instagram Stories and didn’t think much more about it — until I received a direct message from Olena Bulygina, sending me one of the pictures with an added comment that her mother was in the front row. Sure enough, when I looked through Olena’s Instagram Stories, there was the same picture I had shared. And there was a closer crop with the words “hi mom” just above a blond woman depicted between two soldiers and a black heart just underneath (I’m sharing this information with Olena’s permission). As it turned out, when we exchanged some messages, Olena and I knew each other from a workshop that I had taught in Warsaw in 2016. She had been a participant. So what are the odds of that?

There have been similar cross-connections where people could identify loved ones in photographs by photojournalists that they had found on social media. A much more widely known case is that of Serhiy Perebyinis and his family, again in Irpin. Perebyinis had also recognized his family from a picture. He had come across it on Twitter. Unfortunately, unlike in the case of Bulygina’s mother (who made it safely to Kyiv), his family wasn’t so lucky. On their way out of Irpin, the mother and her two children (along with a friend) had been hit by Russian fire and had died. Lynsey Addario had taken the photograph, which later made it onto the front page of the New York Times (I feel that there is a time and place to discuss the ethics of the picture’s use on the newspaper’s front page in more detail, but I am not convinced that I am the best person to do this. In any case, this discussion is beyond the scope of this article). “Perebyinis confirmed that account in a brief interview with The Washington Post early Thursday, explaining that he recognized his family in the photos from their clothes and personal belongings. He was not with his wife and children because he was caring for his mother in Donetsk.”

On 15 March 2022, Alex Lourie published a photograph on Instagram that showed an older woman with a cane. In the caption, Lourie gave her name (Alexandra Trofimovna) and age (86) and detailed some of her life experiences. He later added an edit: “I have pinned a comment to the top by a man I have spoken to, who says Alexandra is his grandmother.” In broken English, Dmitriy (there is no last name) writes, “So this is my Grandma… she is still Oky, Thanks God!!! […] so I’m thankful to the @alexlourie.photo for this post!!! Share this info everywhere…help to stop this war!!!”

Each of these cases is profoundly touching and affecting in its own way. Beyond the human interest, though, these stories also point at the role photojournalism can play when placed into the context of social media. Contrary to frequent claims that traditional journalism always loses out in the wild world of social media, the exact opposite is happening here. The outcome can be a source of grief or joy; someone might find a relative in a picture alive and well, or someone might learn of a terrible personal loss through the relatively anonymous environment provided by social media

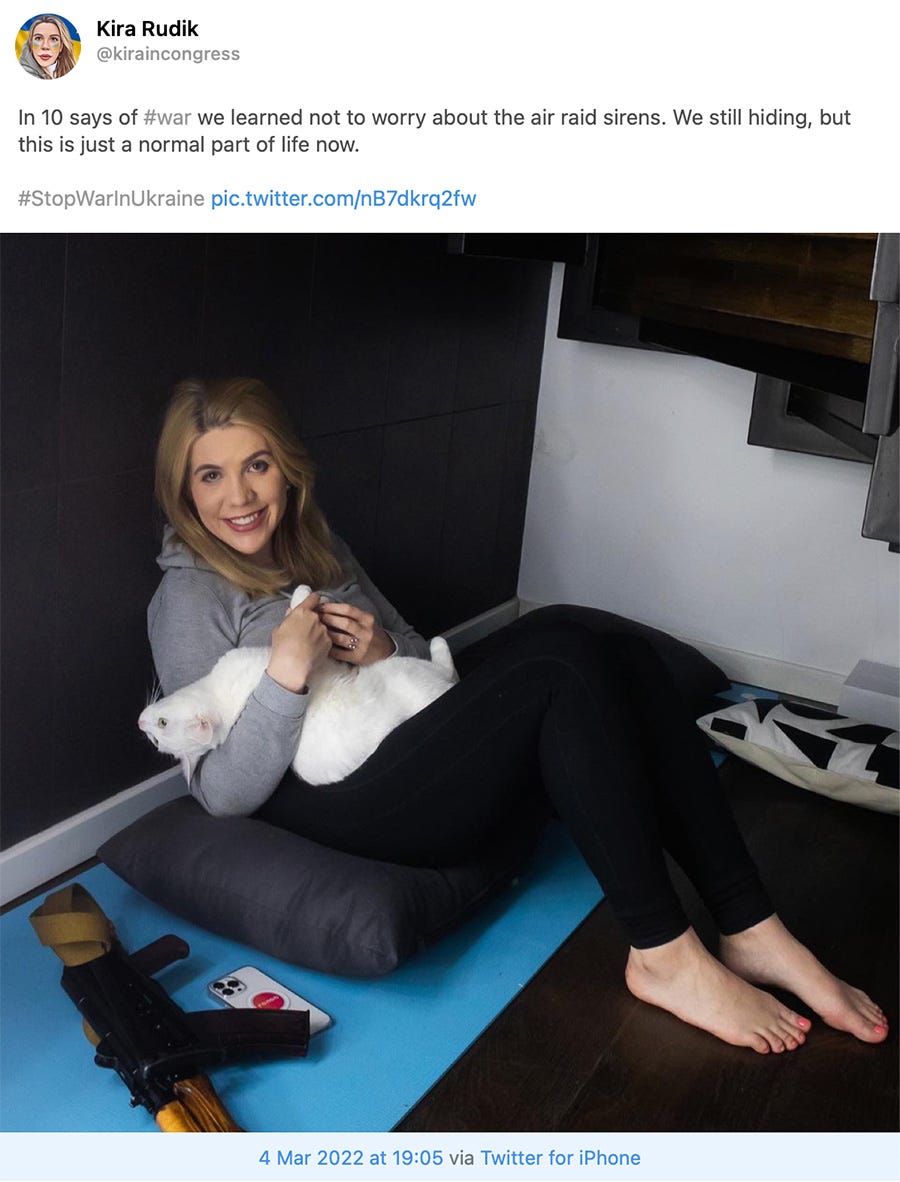

On Twitter, I started following Kira Rudik, who is head of Ukraine’s Holos party that, Wikipedia informs me, is “liberal and pro-European”. Rudik shares her appearances in the media outside of Ukraine. There are frequent patriotic posts (one of them shared Morenatti’s photograph), and there is another type of post, which is how I came across her account in the first place. In this type of post (which appears in English on her Twitter feed and in English and Ukrainian on Instagram), Rudik is seen posing with any number of guns. The associated text typically talks about her weapons training. One post, in particular, struck me. On 4 March 2022, Rudik published a photograph of herself on Twitter with the caption, “In 10 says [sic] of #war we learned not to worry about the air raid sirens. We still hiding, but this is just a normal part of life now. #StopWarInUkraine”. The pictures show her sitting on the ground, underneath what might be a staircase in her apartment. The overall scene is relaxed, even homey, with Rudik barefoot. She is holding her white cat in her arms while smiling at the camera. That camera is not her smartphone, a three-lens iPhone that can be seen lying next to her (with the logo of her party visible on the back of the phone). There is a Kalashnikov rifle next to the phone, its magazine lying across the bottom of the phone.

In obvious ways, Rudik uses what we can consider very standard conventions of so-called influencers to be found all over social media. It’s almost uncanny. The cat, the smartphone (a technological tool as much as a status symbol), the relaxed scene at home, the smile for the camera. If it weren’t for the gun, this could be a picture made by your regular lifestyle influencer (it’s possible that proponents of what is called “gun culture” in the US produce similar imagery, though if they do, I am unaware of it). I follow several influencers on Instagram (the visual language of influencers is a lot more interesting than most photo critics would want to believe), so seeing this picture felt familiar. But it stood out as jarring, given its context.

When I use the word jarring, I don’t mean to imply that I see the photograph and caption as inappropriate. Perhaps the best way to describe my reaction would be to refer to Roland Barthes’ idea of the punctum, the one element in a picture that gets a viewer’s attention. Interestingly, Rudik’s Instagram account has three photographs with slight variations for this particular scene, which makes me wonder even more about who takes these pictures. There must be someone present, possibly a partner or assistant, with whom the production of these pictures is coordinated and who then proceeds to take them. By pointing out the influencer nature of these kinds of photographs, I do not mean to diminish their value. Instead, their visual language can teach us a lot about widely used codes that underpin social media.

Perhaps inevitably, there already is a debate raging over the role of social media, in particular Tik Tok, in Ukraine. The most recent piece I have come across is entitled "The Myth of the First Tik Tok War" by Kaitlyn Tiffany for The Atlantic and the article refers to some earlier articles. I’m not using Tik Tok myself, so I can’t speak to the app’s role or what exactly is on view there. But I do think that articles such as Tiffany’s (and the ones she was responding to) speak more of a journalistic desire to pin a relatively active app to an event, and less of the overall role social media play in both relaying information and connecting information. The latter is of particular interest to me, especially given that discussions around social media too often center on whether some app or platform is still relevant or already past its prime.

Of particular interest to me is the cross-pollination that is increasingly common across different social media platforms. By this I mean that a particular strategy that might have originated on one platform now finds itself in the same or modified form elsewhere. A prime example of this was provided by the selfie videos made by Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky who demonstrated that he and his war-time cabinet were, in fact, present in Kyiv. For a long time, the selfie has been maligned by photography and cultural critics as one of the many manifestations of an egocentric consumerist society (there is, of course, a degree of truth to this claim). That the selfie has the potential to offer a lot more (and frequently does) has largely gone unnoticed. I’m not holding my breath, but the videos made by Zelensky might result in, if not a change in thinking, at least a recognition that seemingly simple social media strategies often are a lot more complex than they might seem.

In contrast to Zelensky, Russia’s dictator has largely produced imagery that evokes a much darker era (which I think many people had considered being a past long gone), but that also shows very little understanding of the reality of 21st-century political communication. Meetings at what looked like impossibly long tables have resulted in fodder for memes, and Putin’s increasingly unhinged monologues evoke echoes of the fictionalized scenes from Hitler’s bunker in the movie Downfall. One particular scene from the movie has become a viral meme itself. Fake subtitles over the German original seemingly have Hitler react to information from a very different context. There already exists at least one version of this meme around the war in Ukraine.

This might sound like a trite point to make, but the effectiveness of Zelensky’s communication in part derives from the sheer ineffectiveness of Putin’s. Beyond these two leaders, though, I’m very tempted to argue that the interplay of different types of visual communication is one of the critical factors of this war. Whether or not this is a TikTok war seems a lot less relevant than the fact that the information reaching us now comprises not only the work of professional photojournalists but also Zelensky’s selfies, Putin’s rants, a bewildering variety of Instagram photographs/videos, TikTok videos, Twitter postings, many popular memes (such as Ukrainian farmers “stealing” Russian tanks), and more. This not only leads to cross-talk between different types of media (such as in the examples I gave at the very beginning), but also to ways to cross-correlate information. Furthermore, I would argue that instead of creating an alternative way to look at the war, one that possibly diminishes the role and value of photojournalism, social media posts actually enhance the work of professional photographers by providing precisely the kind of supplemental information that is out of reach for them.

Jörg Colberg is a writer, photographer, and educator. He is the founder and editor of Conscientious Photography Magazine, and his writing is featured there as well as in photography magazines, catalogues, and artist monographs.

Jörg has taught at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, the Rhode Island College of Design, the University of Hartford, and Neue Schule für Fotografie Berlin.

He is the author of Understanding Photobooks: The Form and Content of the Photographic Book (Routledge, 2016) and Photography’s Neoliberal Realism (MACK, 2020). His first photobook, Vaterland, was published by Kerber Verlag in 2020.