Accuracy, objectivity, and trust in photojournalism

Five lessons from the journalistic failings of Jan Grarup

In April 2022, the award-winning Danish photojournalist Jan Grarup gave an interview in which he outlined the fundamental values of his work:

The most important part for me is to be honest, in terms of what I see, what I photograph, and the people that I talk to. You and I might have different ideas about stories or the information that we get. And that's absolutely fine, but people need to be able to trust my stories, while having their own values and ideas. I'm not here with a political agenda. I know exactly where I stand with my values, in terms of what is going on in Ukraine for example, but for me the most important thing is that people trust my work.

In June 2023, Grarup made his seventh trip to Ukraine, which resulted in a major article (published online on 30 June 2023) and an interview (published online on 30 July 2023) for the leading Danish news publication, Politiken. During that trip, which lasted from 22 June until 6 July, Grarup worked with two fixers, Yehor Konovalov and Alex Babenko.

In mid-August 2023, when Konovalov and Babenko obtained copies of Grarup’s stories, they were shocked. In an interview with Ekstra Bladet in September 2023, Konovalov said:

We had the articles translated, and for every sentence we went through, we just thought: What the fuck! There were so many things that had never happened and were outright lies…It is the first time in the year and a half that the war has been going on that we have experienced that one of the foreign media representatives we have worked with has gone back to his home country and has started to fabricate and lie about things that are happened…And for several reasons we felt a great obligation to get it stopped.

Konovalov and Babenko contacted Grarup to complain. What errors did they find, how did Grarup and Politiken respond, and how did Grarup go from proclaiming his commitment to honesty to being publicly outed for making things up?

In addressing these questions, this article aims to identify lessons from this case for other practitioners. As such, it is less about the individual Jan Grarup and more about the implications of one individual's actions and choices.

Crossing the line in Ukraine

Konovalov and Babenko, the two Ukrainian fixers, say that they found seventeen falsehoods in Politiken's two articles. Some of the main errors were detailed in a report by Journalisten (the publication of the Danish Association of Journalists):

In the article on July 30, Jan Grarup says that he has fired a mortar shell at Russian positions. It is not correct. Jan Grarup wrote a 'greeting' to the Russians on the grenade, but the firing itself was carried out by a Ukrainian soldier.

In the same article, two episodes are reproduced as if Jan Grarup himself had experienced them. One concerns how Ukrainian soldiers intimidate Russian prisoners of war by debating in front of them whether to execute them or cut off their hands. The second is that the 3rd Assault Battalion lost 40 men in combat in a single night. Both parts are episodes that Jan Grarup has had reproduced by a source. He has not experienced them himself, and the loss figure is not about the 3rd Assault Battalion, but about another unit.

In the interview on 1 July [published online on 30 June], Jan Grarup says that he and his Ukrainian team visited the pizzeria RIA in Kramatorsk, three hours before it was hit by Russian missiles on 27 June. However, the visit took place the day before the missile attack. It also said that there was a group of Colombians at the restaurant, but there wasn't.

The first of these examples is an extraordinary moment. A photojournalist firing a mortar while reporting on a military unit would be a major ethical transgression. But so is a photojournalist writing on a mortar shell that the military fires. Remarkably, Grarup posted an image of the shell (see below), with his message visible, on his Instagram account, where it remains at the time of writing despite the ensuing controversy.1

Politiken responds

It is unclear how Grarup responded when his Ukrainian fixers contacted him on 16 August to detail the inaccurate elements of the Politiken articles. Given that the Politiken editor Christian Jensen did not know of their concerns until the fixers sent Jensen an email at the end of August, Grarup certainly took no action to make the newspaper aware of the problems. He did, though, post on Instagram on 25 August: “Another shitstorm coming my way - some will say it is fair - others not.. but still Proud that President Zelenskiy is sharing my work. #Slavaukraini.”

Two weeks after Politiken learned of the problems with Grarup’s interview and statements — and following a series of meetings with Grarup — Politiken announced it would no longer work with Grarup in its coverage of the war in Ukraine. In his public statements, Grarup admitted the mistakes, apologized, and showed an understanding of Politiken’s position: “I have nothing to complain about Politiken. I understand 100 percent that they no longer want to work with me. Journalistic integrity and credibility are important.”

Amalie Kestler, Politiken’s editor-in-chief, said that this decision did not affect anything beyond Grarup’s Ukraine coverage:

This is a decision that concerns Ukraine. Jan Grarup is a freelancer, and I have been very happy with our collaboration. I wouldn't rule out that we could collaborate with him in the future elsewhere in the world if he goes somewhere else and offers us some material. Then we will look at it in the specific situation.

But if you don't want to bring pictures of Jan Grarup from Ukraine, why do you want from other places?

We have no reason to believe that there is anything wrong with Jan Grarup's photos. It relates to some concrete information he has given in some interviews. And then it is about the fact that he himself has declared that he is no longer objective in the coverage of the war in Ukraine.

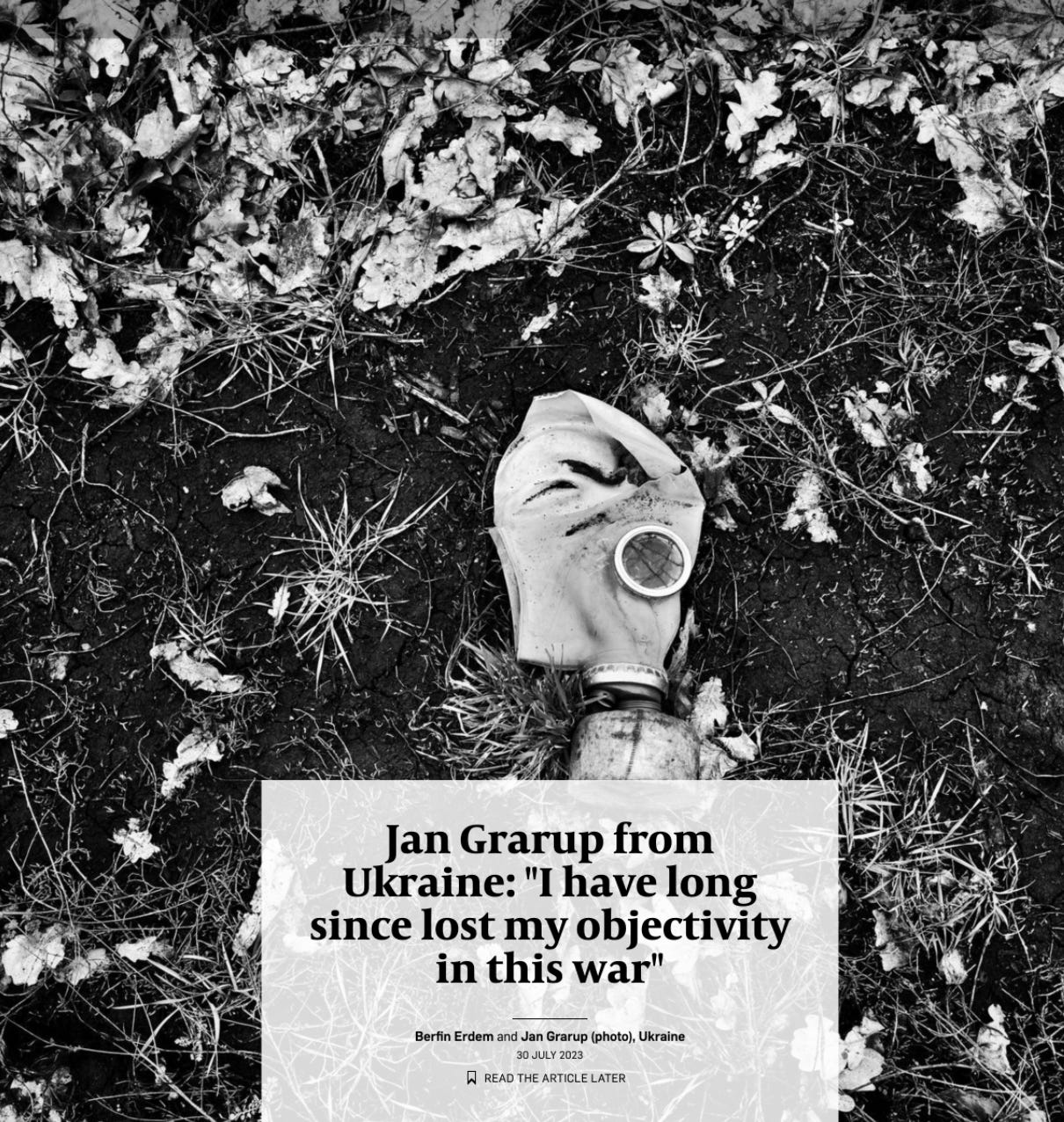

The last line of Kestler’s comments stands out. Grarup did declare he was no longer objective in relation to Ukraine. But that should not have come as a surprise to anyone at Politiken, as the original headline for the 30 July interview in Politiken was a direct quote: “Jan Grarup from Ukraine: ‘I have long since lost my objectivity in this war.’”

Furthermore, the interview embedded Grarup’s Instagram post with the signed mortar shell and quoted Grarup at greater length:

‘I have long since lost my objectivity in this war. I am 100 percent on the Ukrainian side. I wish nothing good for these Russian soldiers or for the Russian regime,’ says the experienced photographer, who adds that he has always managed to distance himself from this kind of thing.

He is not proud of what he did, he says. On the contrary:

‘But I don't want to lie about it. I will have to show who I am.'

Politiken used Grarup’s statement about losing objectivity against him despite promoting it as a virtue only weeks earlier. Tellingly, although this interview is still available on the Politiken website, the (translated) headline has been changed to read: “Jan Grarup from Ukraine: ‘I did something on this trip. And I get 100 percent trouble for that.’”

Extending the investigation

The controversy surrounding Grarup’s 2023 Ukraine reports was extensively covered in Denmark, and with that coverage came allegations of problems in more of Grarup’s written reportage. Politiken also combed through Grarup’s archive and found issues with even some of the most benign images of animals and Christmas hats he produced for the newspaper.

More importantly, did Grarup exaggerate his proximity to a 1994 car bomb explosion in Johannesburg? Was his 2000 photo essay “The Boys from Ramallah” flawed, as Anne Lea Landsted’s unheeded warnings to Politiken back in 2001 argued?

Most significantly, following an episode of “The Reporters” on 24syv, Grarup’s Rwanda reporting was questioned. Is it correct — as Helle Maj and Jørn Stjerneklar conclude after a five-week investigation — that Grarup “exaggerates, dramatizes or outright fabricates his stories from Rwanda”?

Politiken now believes so and revealed that in 1994, Grarup was in Rwanda for only two days, not the long period he claimed. An investigative report on Grarup’s past work — commissioned by the editor-in-chief and conducted by the former investigations journalist John Hansen — reached a number of damning conclusions about an anniversary story. An editorial note attached to Grarup’s 2019 photo essay commemorating the Rwandan genocide 25 years later states:

Politiken no longer vouches for the content of this essay, as the premise has been shown to be incorrect and essential elements of the story erroneous.

According to an investigation by journalist John Hansen for Politiken, Jan Grarup's alleged week-long presence in Rwanda during the actual genocide in 1994 cannot be confirmed.

In addition, specific scenes and route descriptions in the essay have been shown to be seriously flawed:

Jan Grarup did not spend two or three weeks in Rwanda during the genocide in 1994. He was there for a few days, when he did not drive around alone, but was with a group of international press people.

He did not come to the church in Nyamata a few hours after a violent massacre had taken place there. The massacre had taken place several weeks before Jan Grarup's visit to Rwanda. There are also untruths in his rendering of two women's experiences during the genocide.

When Politiken has chosen not to delete the entire text, it is due to a desire to stand by the editorial mistakes that have been made in this context, as a number of information in the text could have been checked.

[Politiken apologises].

Read John Hansen's study here .

Read the editor-in-chief's comment here.

Grarup apologized for these errors. In a Facebook post, Grarup said while he did not intend to lie, he acknowledged inaccuracies in his story:

‘My memory and my judgment have failed. The responsibility for that is mine, and I take it,' writes Jan Grarup.

He describes his coverage of the genocide in Rwanda as ‘the most violent weeks of my working life’ and says that it subsequently gave him PTSD and led to an alcohol addiction.

‘I had no notes with me from Rwanda, and when I revisited Rwanda 25 years later and wrote my essay, I tried to tell the story as best I could.’

The “rock star”

With the fact-checking of Grarup’s archive producing more and more issues to confront, how were decades of falsehoods enabled? Danish photographer Klaus Holsting said various factors produced a “star hype” around Grarup. Numerous media organizations loved the story of the photographer who could attract a large public audience eager to hear his pathos-filled dramatic experiences in conflict zones. Interviewers felt Grarup was like a “rock star,” an aura aided and abetted by the photographer’s portraits showing off his tattooed torso on the “Made by Grarup” website (where the logo, a signed facsimile of a rubber stamp, suggests authenticity and exclusivity). Politiken has actively participated in this branding, with their prominent placement of Grarup’s conflict imagery buttressed by personal profiles of the “star photographer” that laid bare a bad boy persona and several instances of problematic behavior.

These profiles also reveal that Grarup has been diagnosed with PTSD and struggled with alcohol and drug addiction, conditions shared with many other conflict photographers. These factors cannot excuse Grarup’s working practices, but neither did they make Politiken any more rigorous in handling Grarup’s reportage. As John Hansen notes in his investigation for Politiken:

Jan Grarup has made no secret of the fact that he has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress syndrome, PTSD, and that he has had periods of heavy consumption of cocaine and alcohol as a result of violent experiences as a photographer in war and disasters. Two editors say that in the summer of 2023 they discussed how mentally damaged Jan Grarup is by the brutal experiences he has been subjected to in his work, but without this leading to decisions about additional fact-checking or the decision to continue cooperation.

The lessons

What are the lessons we can draw from this case? As I noted at the outset, this article is less about individual failings and more about the implications of their actions and choices. No doubt there will be other lessons in addition to those listed here, but I would argue the following are among the main takeaways from the Grarup case:

1. It’s not just about your pictures

For photographers who want to be visual journalists, accuracy requires much more than producing images that are not manipulated or staged. One notable element of the Grarup case is that his failings relate to interviews and texts that accompany his pictures. None of his photographs per se have been questioned; it is the falsehoods and inaccuracies in the reports about his images that have been exposed. Journalism is the art of verification, and visual journalists need to be able to write as well as photograph. You have to be able to verify everything you say and write.

2. Be objective, but understand what objectivity means

Objectivity has to be one of the most misunderstood issues in journalism. As a concept, it has a long history, one so complex that Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison wrote a brilliant 500-page book on the subject! We don’t need to delve into that here; instead, we should note that “being objective” is not about being free of bias, commitments, or opinions. As Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenthal have written:

Objectivity [calls] for journalists to develop a consistent method of testing information—a transparent approach to evidence—precisely so that personal and cultural biases would not undermine the accuracy of their work….in other words, the method is objective, not the journalist. The key [is] in the discipline of the craft, not the aim.

Objectivity as a method requires that journalists do original reporting and research, take and keep extensive notes, record their interviews, and be transparent about their methods, motives, and sources. This approach and these records together make up the art of verification.

3. Take your time

Research, writing, and verification takes time. You need more than two days in a place to report meaningfully. Make a virtue of the fact visual journalists arrive late. When citizens carry smartphones, they are the ones present in the moment when something happens. But they do not provide the context, meaning, or implications of what they are quickly snapping. Only visual journalists can do that. On balance, you will spend much more time researching, interviewing, and writing than photographing or videoing. Of course, the resources available to you influence how much you can spend in a place, but if you cannot afford to be there for some time, ask yourself if it is worth going.

4. Exercise humility and be trustworthy

Practicing the art of verification requires humility rather than machismo. None of us can know everything, no matter how much time we spend investigating. If you are constructing a “brand,” make it one that is known for being trustworthy. As Charlie Beckett has argued:

Build a relationship over time where people have expectations that you will deliver relevant, reliable and accessible journalism…Show them your workings, admit and correct your mistakes. Be honest about what you don’t know and listen to what your users say interests them. Try to be diverse, accurate, empathetic, and purposeful. Be constructive as well as critical. Be ethical, moral, and political without being partisan. But don’t run advertising campaigns saying how important journalism is. Don’t advocate for media literacy education on the basis that people are too dumb to realize how great and valuable your work is. First of all, get yourself more literate about technology, your topic, and your public.

5. Legacy media needs to do its job better

Too often, established media organizations fail to practice the art of verification. The independent investigation of Grarup’s work for Politiken found there had been “insufficient fact-checking” throughout the years they published his work and too much reliance on assumptions of personal trust. Politiken says it is changing its editorial guidelines to codify that records such as flight tickets, names and phone numbers of fixers, and details of contacts are provided to editors. However, freelancers should have their own established records and practices and should not rely on media organizations to set out what is needed for verification.

War correspondents have historically had a mixed record of accuracy in their accounts of conflict. Among them, the stories about Robert Capa’s iconic D-Day photographers have long been misrepresented and embellished, the famous Polish author Ryszard Kapuściński has had the veracity of his books questioned, and the Danish war reporter and fiction writer Jan Stage was known by his editors to be “creative” with the facts.

In the past, these storytellers — and perhaps, as Jørgensen writes, approaching reporting as a “story” is part of the problem — could flourish in the absence of fact-checking. Today, when the structures of communication have changed, and fixers can instantly review your writing, inaccuracies can be fatal. Given the proliferation of disinformation in our world, such inaccuracies should be fatal. To be trusted — as Jan Grarup once said was his desire — requires transparent, rigorous verification to be the basic condition for visual journalism.

The complete caption of Grarup’s 30 June 2023 Instagram reads:

‘Today I did something I have never done before. I wrote a message on a mortar shell before it was launched at a russian position near Bakhmut - I wrote for Anna and Yullia, the two 14 year old twins who was killed yesterday. I could have written a thousand names but today I was present at their funeral and I hugged their mother and father and felt so Angry and powerless - this shell fired from friends in @gang__of__gunners was for them - I hope it reached its target. I am sorry, but honest… rest in peace Anna and Yullia -freedom for Ukraine - Slava ukraini 🇺🇦 ❤️ #warinukraine #war #innocent #russianinvasion #russiaisaterroriststate #children #twins #twinsisters #neverforget #freedom #pizza #kramatorsk #soverignty #defenders #victims #fuckoff #anger #revenge #picoftheday #photooftheday’

The first comment on the post was from the Australian photojournalist Dean Sewell:

‘This is revolting Jan. As a fellow photojournalist who’s early development coincided with your own, I was drawn to and have followed your progress with much interest and sought inspiration from you, your tenacity to deliver powerful work under extreme situations and your distinct artistic approach. I considered your work and practice to be of the highest level, both objectively and ethically. This crosses the line for me. I don’t believe you have the right in acting on behalf of two dead Ukrainian teenage girls no matter how tragic their deaths. You don’t know beyond assumption who that mortar might maim or kill and most certainly, you deny those two girls any agency by sending off a mortar, even into enemy positions on their behalf. What if they, having already grown up for most of their lives in a war zone, decided that they would have devoted their lives to pacifism and headed the global anti-war movement? You simply don’t know. And as for your cheerleading respondents to this post, excusing you and applauding you for this deed - Well, I am left speechless. What next, workshops in ethics and photojournalism? I understand perfectly well the powerlessness and anger that can consume one witnessing such gross violations of human rights, but here, you let your professional conduct slip, and disappointingly so.’