Erasure as a Method of Exposure

Arturo Soto considers how and why explicit violence on the Mexico-American border should be seen through a review of Alejandro Morales’ “El retrato de tu ausencia”

One of photojournalism’s imponderable questions is whether violent acts should be depicted explicitly. This is a controversial issue that should be discussed, although, in practice, some media outlets consistently produce graphic imagery regardless of how sensitive the situation is. In a region like the Mexican-American border, simply avoiding documenting violent acts is also problematic, as it can aid the federal and state governments in denying accountability or manipulating information (and that’s without considering the dark arts of state censorship).

Whereas American and British tabloids abuse people’s privacy for profit, in Mexico they exploit their readers’ appetite for gruesomeness. The tabloids are a necessary evil in Ciudad Juárez, where the boundary between serious and sensationalist journalism has long been blurred. Their graphic coverage is certainly calibrated for financial gain, but their articles are also used in sociological studies as an extreme reflection of the zeitgeist or as an additional source to determine the number of murders in the city. The degradation of everyday life along border cities like Juárez prompted the writer Sayak Valencia to coin the term ‘gore capitalism’ to describe how “death has become the most profitable business in existence.”

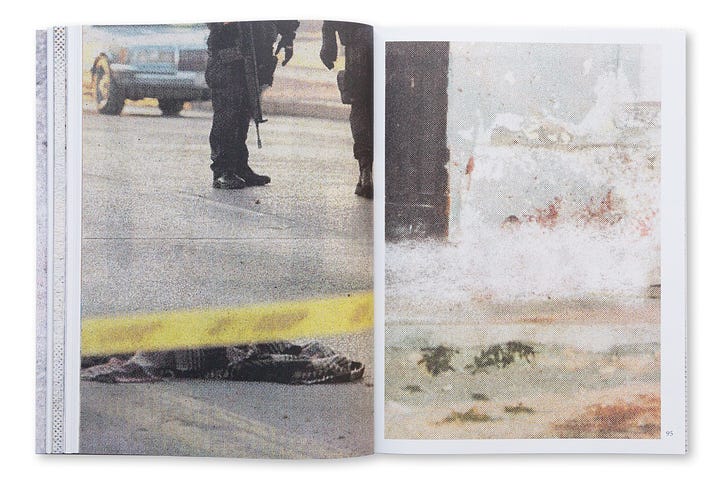

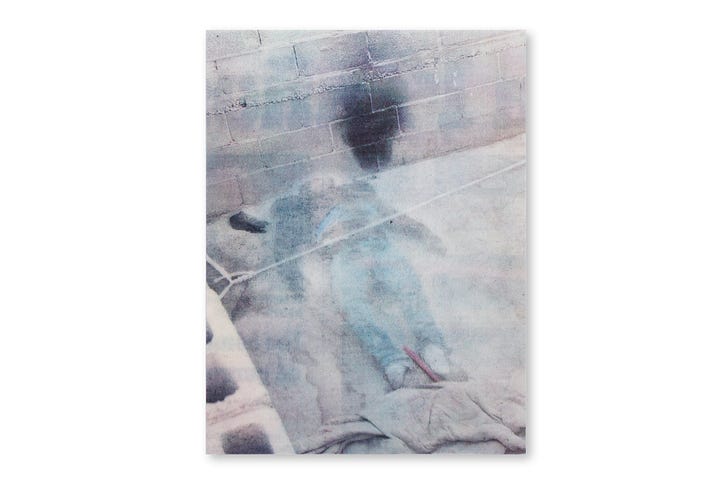

The photobook El retrato de tu ausencia (The Portrait of Your Absence) by the multidisciplinary artist Alejandro Morales adopts a conceptual approach to question what we gain from explicit images of murder, prompting us to meditate on the ever-changing ethics of representation. The genius of his artistic strategy lies in its simplicity: Morales used a gum eraser to remove the corpses from photographs appropriated from the newspaper PM. The erasure leaves a trace on the paper akin to freshly applied plaster, with the text from the verso often seeping through the area of the image where the dead body used to be, complicating its readability. The resulting palimpsest problematizes the notion that more information leads to a greater understanding. Morales believes his intervention produces “a more dignified form of death.” He saved the 14 grams of eraser residue, which he likens to ashes, and exhibited them in a plexiglass cube as sculptural work.

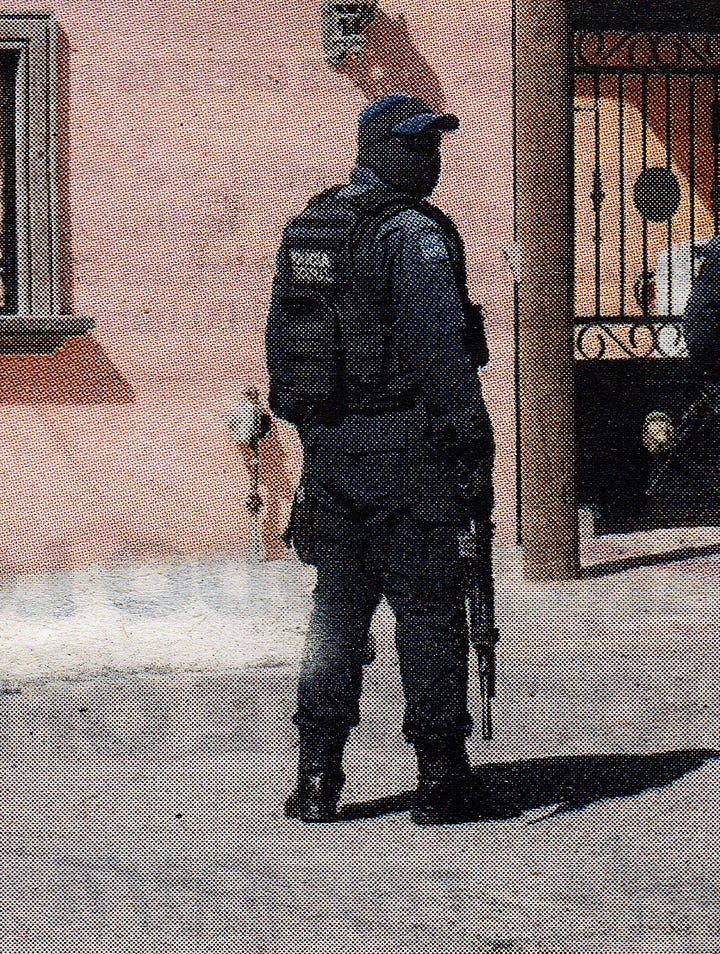

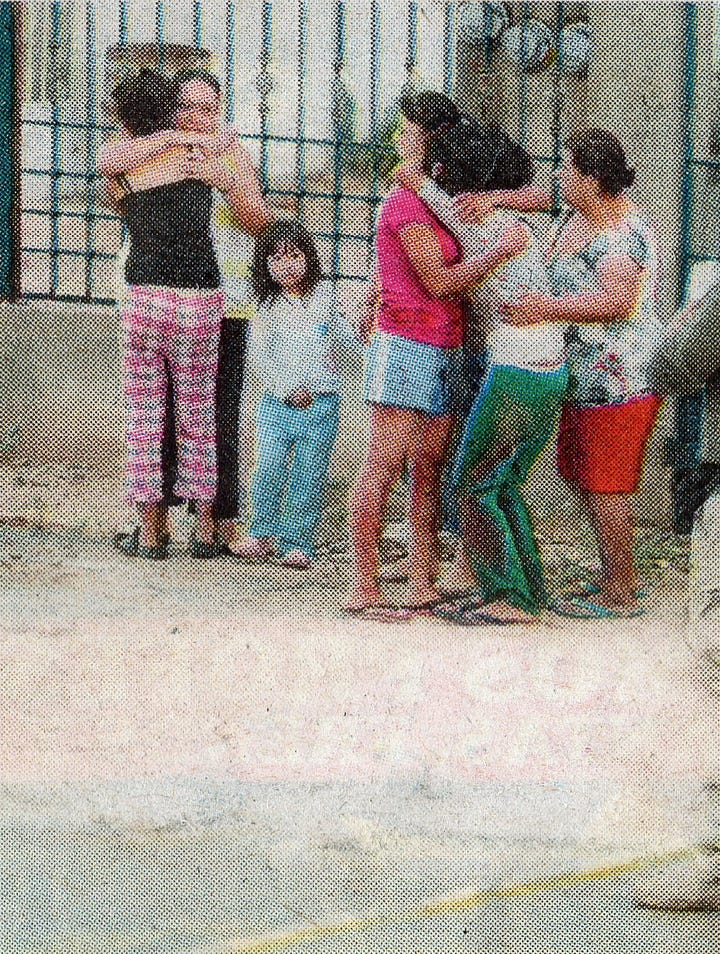

With the corpses removed, details in the crime scenes become the focus of attention. Grievers, police officers, stray dogs, and old cars are thought-provoking elements that readers could have easily overlooked as background information. In other pictures, the harsh topography of the desert is all we can see. Blood only features in a few instances, but even then, most of the shock value has been drained from those images. Overall, the erasure also implies the affective void in the victims’ families, as well as the legal one caused by ineffective investigations that dissolve the victim’s individuality in official paperwork. The poorer the victim’s family, the lower their chances of achieving justice or even closure, which depends on knowing the truth of the crime (especially painful when the death resulted from collateral damage).

El retrato de tu ausencia alludes to the complicated search for truth using a medium where appearances can be easily manipulated. But if a straight photograph already constitutes an act of manipulation – cropping is the easiest way of editing reality – how can Morales’ images be truthful when their conceit is so overt? The way I see it, these pictures aim to shift our attitude toward the framework of truth in photojournalism. Instead of only looking at the sensationalist element they intended to represent, we are forced to analyze the periphery of the images, which can be more meaningful and complex than the photographers visualized.

Every detail is crucial in a book as sparsely designed as El retrato de tu ausencia. The cover features a lenticular print that cleverly displays and conceals a dead body, the only instance in the book we encounter one. Newsprint is used to reproduce the tabloid’s texture, with the pictures’ half-tone pattern reminding us of their original purpose. On the inside cover, an index lists the book’s seventy-four photographs, each titled after the headline of the article they illustrated. Punchy lines such as Dejan cuerpo a media calle (Body left in the middle of the street) or Le sacan los sesos (They blew out his brains) stress the tabloid’s exploitative nature while suggesting the narrative we can’t see.

El retrato de tu ausencia is a reaction to the depiction of violent acts that stem from drug trafficking, illegal migration, labor exploitation, and the weakening of public institutions that have characterized Juárez’s recent history. As such, Morales’ concept comes with a catch: to fully appreciate this book, viewers must be familiar with this history and the kind of violent images he purposefully subverts. His work raises the question of whether political art should provide adequate contextual information for audiences to understand the issues at hand.

Art’s pedagogical responsibility is another imponderable question, but since the impact of these images comes from what they don’t show, the creative decisions taken by Morales might make the difference between understanding his discourse or looking at them as oddities. At the very least, Morales has set the ground for us to reflect, irrespective of our familiarity with the northern Mexican border, on how the images produced by the media affect what we deem truthful.

Arturo Soto is a Mexican photographer, writer, and educator. He has published the photobooks In the Heat (2018) and A Certain Logic of Expectations (2021). Arturo holds a Ph.D. in Fine Art from the University of Oxford, an MFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York, and an MA in Art History from University College London. Arturo lives in Wales, where he is a Lecturer in Photography at Aberystwyth University.

Arturo writes a series of reviews on Latin American photographers for Dispatches: The VII Insider Blog. Check out his other articles:

The Possibilities of the Actual: Adriana Lestido’s "Metropolis"

Pablo Hare: Sites of Exploitation in Peru

Feeling Out the Past: Graciela Iturbide’s “Heliotropo 37”

A Masked Profession: Federico Estol’s Shine Heroes

The Persuasions of Disobedience: Ana María Lagos

Messages of Angst and Hope: Notas De Voz Desde Tijuana

The Politics of Window Shopping: Pablo López Luz's Baja Moda

Life in a Lawless Town: Juan Orrantia’s A Machete Pelao

The Disenchanting Hunt for the Truth: Christo Geoghegan’s “Witch Hunt”