The Poetics of Infrastructure: Thomas Locke Hobbs’ "Rampitas"

Arturo Soto examines how Medellín’s unequal urban planning is represented through images of informal architecture.

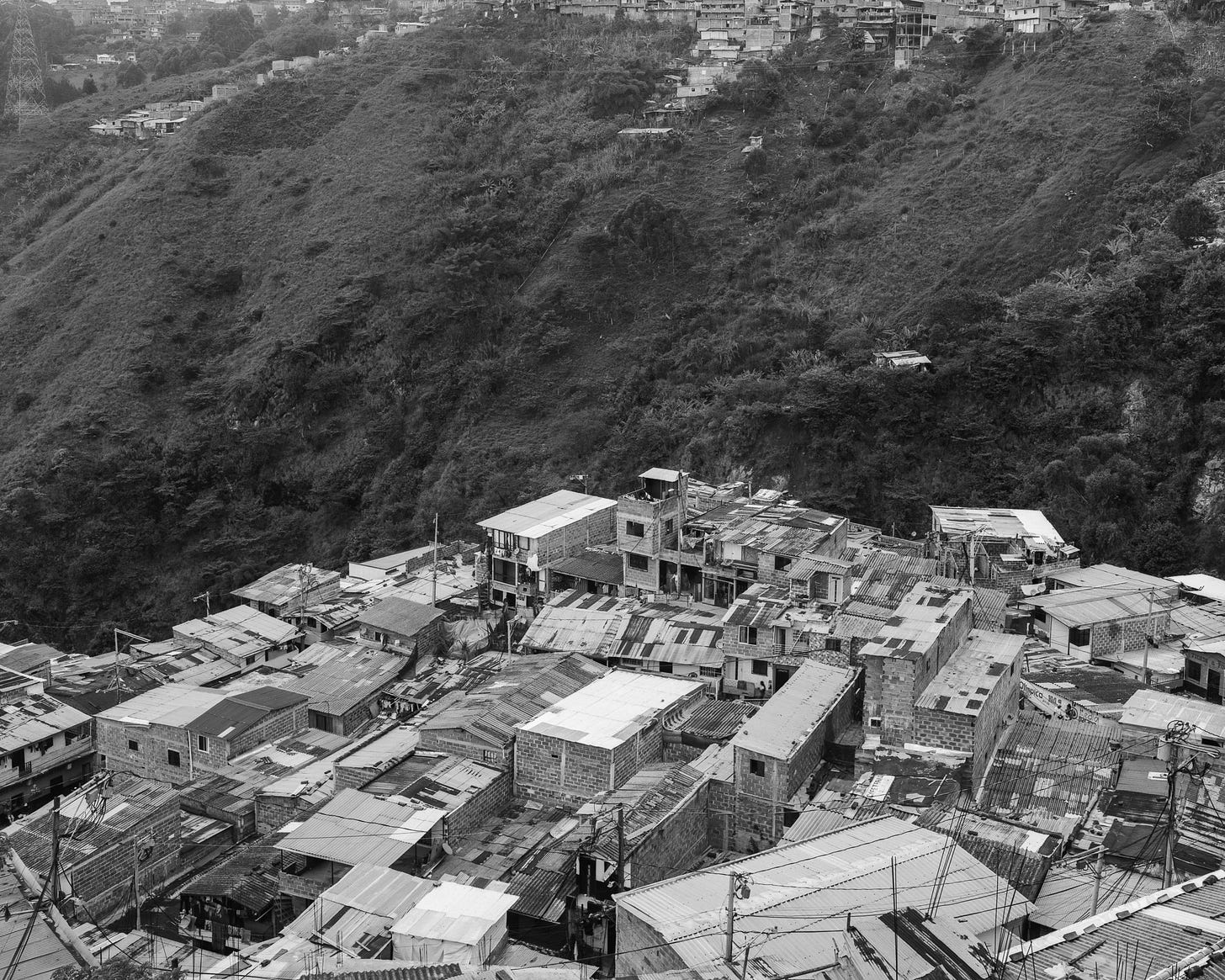

Thomas Locke Hobbs’ book Rampitas works like a metonym – that rhetorical figure in which a detail stands for the whole – with the small cement ramps of the title representing Medellín’s unequal urban planning. This minor infrastructural appendage has become ubiquitous since people must walk their bikes, scooters, and mopeds through the city’s steep hills. It won’t be surprising to know that these ramps are found primarily in working-class neighborhoods built on an unfavorable topography with tenacity and stubbornness. Locke Hobbs, an American living in South America for more than a decade, photographed in areas categorized as Strata II and III (following the Colombian vernacular), relying on local guidance to avoid trespassing invisible borders where his large format camera would have been unwelcome.

These ramps are among the wide range of informal architecture that constitute the culture of autoconstrucción. The concept of do-it-yourself (DIY) is probably the closest in English, except that its usage doesn’t connote socioeconomic disadvantage or reliance on collaboration to attain communal well-being. In essence, autoconstrucción is deeply rooted in a disillusionment towards policy, though standing at the opposite end of apathy via an ethos of ‘getting things done’ (however, the book features an instance of an official ramp, identifiable by how it sits flush with the steps). The utilitarian purpose and rough appearance of the ramps tend to make them go unnoticed, which confirms how integral they have become to the social dynamics of the city.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Rampitas is the sheer variety of designs and configurations of these ramps, integrating patterns to improve traction when the pavement gets wet. Others are more comical, looking like pitcher mounds made of solidified putty or miniature platforms for children’s games. The most compelling images make visible the multiplicity of directions in which people circulate with their vehicles, but with a visual flair that recalls the spatial contradictions of an Escher painting. Most of the pictures are close-ups that decontextualize the ramps from their environment, evoking the contrasty compositions of modernist photographers like Jaromir Funke, although Locke Hobbs claims a closer affinity with the postwar landscapes of Toshio Shibata and the textural formalism of Aaron Siskind.

On an ontological level, the distinctiveness of some ramps makes one ponder if aesthetic considerations informed their design and whether these decisions were mainly intuitive. As the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher demonstrates, even the most utilitarian structures disclose an aesthetic that reflects cultural values, an idea the German duo suggested via the title of their first book, Anonymous Sculptures. The raison d'être for these ramps may be to achieve a durable functionality, but the fact that some of them flirt with artifice allows Locke Hobbs’ documentation to add another layer of ambiguity to how we perceive them. For instance, one of the most accomplished pictures in the book depicts an eclectic collection of circles and lines inscribed onto the concrete. Their apparent randomness is an opportunity to reflect on who gets to leave a lasting mark in an urban environment and, by extension, how informal constructions can sometimes last much longer than authorized ones.

It is essential to mention that this is an accordion book, a playful approach that breaks with the rigidity of typologies like the Bechers’. Rampitas is printed on both sides, making the handling and turning of the paper folds integral to the experience of this documentary project as an object. As with any accordion book, there is the possibility of unfolding it all the way to turn it, as the photographer Dayanita Singh has claimed, into an ‘exhibition,’ but I presume most people will use the provided yellow rubber band to secure the folds once they are done flipping through them. The publication’s size embodies an unusual kind of modesty that is well complemented by an attractive design and layout, with distinctive blue margins between the images that reference an earlier handmade maquette in which Locke Hobbs used blue tape to hold the folds together.

While the book emphasizes the material and aesthetic character of the ramps, it also features a couple of landscapes and portraits that function as cinematic cutaways. Seeing the city’s trademark hills and funicular makes it clear just how necessary these ramps are, whereas a charming scene with a boy standing still atop a flight of stairs allows us to imagine the lives of those who inhabit these places. After all, Medellín is probably the most important example of urban regeneration in recent times in Latin America, and a significant part of that success is owed to the efforts of the people from the barrios shown in these pictures.

Like the rest of Lock Hobbs’ projects, Rampitas is calibrated to open up a space for reflection rather than engage in activism or pedagogy. As such, the book does not include an essay or any other kind of critical commentary explaining its content. This means viewers must determine for themselves whether the book’s underlying tone is an optimistic one. However, it’s reasonable to conclude that the ramps are evidence of the ingenuity and adaptability of their makers and that autoconstrucción, for all its shortcomings, has the potential to correct some of the deficiencies of top-down urban planning to attain a more functional city.

Arturo Soto is a Mexican photographer, writer, and educator. He has published the photobooks In the Heat (2018) and A Certain Logic of Expectations (2021). Arturo holds a Ph.D. in Fine Art from the University of Oxford, an MFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York, and an MA in Art History from University College London. He lives in Wales and is a Lecturer in Photography at Aberystwyth University.

Arturo writes a series of reviews on Latin American photographers for Dispatches: The VII Insider Blog. Check out his other articles:

The Possibilities of the Actual: Adriana Lestido’s "Metropolis"

Pablo Hare: Sites of Exploitation in Peru

Feeling Out the Past: Graciela Iturbide’s “Heliotropo 37”

A Masked Profession: Federico Estol’s “Shine Heroes”

The Persuasions of Disobedience: Ana María Lagos

Messages of Angst and Hope: “Notas De Voz Desde Tijuana”

The Politics of Window Shopping: Pablo López Luz's “Baja Moda”

Life in a Lawless Town: Juan Orrantia’s “A Machete Pelao”

The Disenchanting Hunt for the Truth: Christo Geoghegan’s “Witch Hunt”

Erasure as a Method of Exposure

The Political Price of Dreams: Pablo Cabado’s "Little Suns on Earth"

The Infinite Resonances of a Single Word: Marisol Mendez’s "Madre"